|

DUPONT - PLASTICS

According

to their website, DuPont is a leading innovator of thermoplastics, ethylene copolymers, elastomers, renewably-sourced polymers, high-performance parts and shapes, as well as resins that act as adhesives, sealants, and modifiers.

Following WWI, DuPont produced synthetic ammonia and other chemicals. DuPont began experimenting with the development of cellulose based fibers, eventually producing the synthetic fiber rayon. DuPont's experience with rayon was an important precursor to its development and marketing of nylon.

DuPont

use their world-class expertise across multiple polymer platforms to integrate cutting-edge science, design, manufacturing excellence, and processing technology to give shape to smarter ideas for today and tomorrow.

Between now and 2050, the world’s population will climb to 9 billion. This increasingly complex world places growing demands on our planet’s resources.

DuPont find solutions for needs as diverse as more plentiful, healthier food, renewably sourced advanced materials, ample energy, and better infrastructure and transportation.

Their strengths in Agriculture & Nutrition, Bio-Based Industrials, and Advanced Materials enable

them to address the full scope of these challenges.

Food security around the globe becomes vitally important as our

population

increases. One in seven people on earth goes to bed hungry each night. Ensuring that enough healthy, nutritious food is available for people everywhere is one of the most critical challenges facing mankind. We commit 60% of our research and development dollars to ensuring that the world’s growing population has enough to eat.

SUSTAINABILITY

Most companies in the plastic business operate responsibly toward the environment, seeking to limit ecological damage beyond their control ......

We cannot do without plastics in our modern society. They are incredibly versatile, extending the capabilities of mankind. But plastic is getting bad press from a lack of recycling efficiency in many countries where significant quantities are being flushed out to sea via rivers and other coastal dumping.

There is nothing wrong with plastic if it is disposed of carefully. Oil derived plastics are a finite resource and non-renewable demanding special attention, as with the changeover from burning fossil fuels to renewables.

This gives us another good reason to develop a system for making the best use of plastic, and this includes recycling it way more effectively than before. We cannot afford to waste plastic that is in our oceans, and we are talking about at least 8 million tons a year of the stuff going out to sea.

FAST FOOD SLOW DEATH - It's not just fast food, it is our exploitative society that is poisoning the planet, without thought for the consequences. We've been living at artificially low prices at the expense of killing other life on earth. Eat cheap now and suffer expensively later, with health services picking up the tab and costing the taxpayer more than if we'd dealt with ocean dumping up front. We are talking here about the consequences of eating toxic fish. Technically, it is possible to remove plastic from seawater. There are two projects currently trying to achieve this, the Ocean Cleanup Projects of Boyan Slat and his giant floating booms, and the Cleaner Ocean Foundation and SeaVax.

It's easy to dismiss plastics as cheap and nasty materials that wreck the planet, but if you look around you, the reality is that we depend on it. If you want cars, toys, replacement body parts, medical adhesives, paints, computers, water pipes, fiber-optic cables, and a million other things, you'll need plastics as well.

If you think we struggle to live with plastics, try imagining for a moment how we'd live without them. Plastic is pretty fantastic. We just need to be smarter and more sensible about how we make it, use it, and recycle it when we're done with it.

Most plastics are synthetic, they'd never spontaneously appear in the natural world and they're still a relatively new technology, so animals and other organisms haven't really had chance to evolve so they can feed on them or break them down.

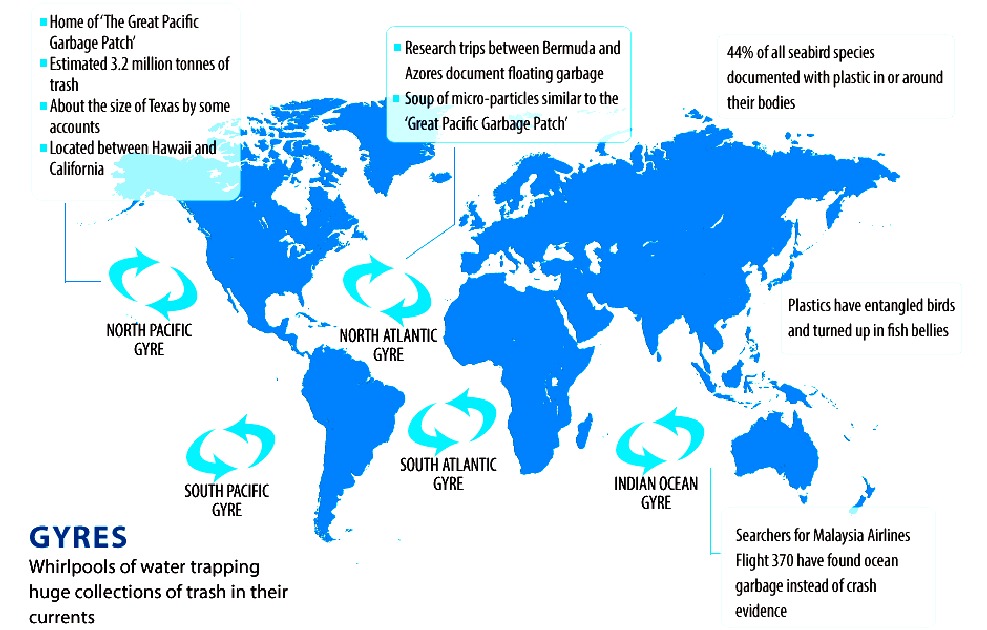

Since a lot of the plastic items we use are meant to be low-cost and disposable, we create an awful lot of plastic trash. Put these two things together and you get problems like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a giant "lake" of floating plastic in the middle of the North Pacific Ocean made from things like waste plastic bottles.

How can we solve horrible problems like this? One solution is better public education. If people are aware of the problem, they might think twice about littering the environment or maybe they'll choose to buy things that use less plastic packaging.

Another solution is to recycle more plastic, but that also involves better public education, and it presents practical problems too (the need to sort plastics so they can be recycled effectively without contamination). A third solution is to develop bioplastics and biodegradable plastics that can break down more quickly in the environment.

NYLON

DuPont's invention of nylon spanned an eleven-year period, ranging from the initial research program in polymers in 1927 to its announcement in 1938, shortly before the opening of the 1939 New York World's Fair.

The project grew from a new organizational structure at DuPont, suggested by Charles Stine in 1927, in which the chemical department would be composed of several small research teams that would focus on “pioneering research” in chemistry and would “lead to practical applications”.

Harvard instructor Wallace Hume Carothers was hired to direct the polymer research group. Initially he was allowed to focus on pure research, building on and testing the theories of German chemist Hermann Staudinger. He was very successful, as research he undertook greatly improved the knowledge of polymers and contributed to science.

After these discoveries Carothers’ team was made to shift its research from a more pure research approach investigating general polymerization to a more practically-focused goal of finding “one chemical combination that would lend itself to industrial applications”.

It wasn't until the beginning of 1935 that a polymer called "polymer 6-6" was finally produced. The first example of nylon (nylon 6,6) was produced by Wallace Carothers on February 28, 1935, at DuPont's research facility at the DuPont Experimental Station. It had all the desired properties of elasticity and strength. However, it also required a complex manufacturing process that would become the basis of industrial production in the future.

DuPont obtained a patent for the polymer in September 1938, and quickly achieved a monopoly of the fiber. Carothers died 16 months before the announcement of nylon, therefore he was never able to see his success.

The production of nylon required interdepartmental collaboration between three departments at DuPont: the Department of Chemical Research, the Ammonia Department, and the Department of Rayon. Some of the key ingredients of nylon had to be produced using high pressure chemistry, the main area of expertise of the Ammonia Department.

Nylon was considered a “godsend to the Ammonia Department”, which had been in financial difficulties. The reactants of nylon soon constituted half of the Ammonia department's sales and helped them come out of the period of the Great Depression by creating jobs and revenue at DuPont.

DuPont's nylon project demonstrated the importance of chemical engineering in industry, helped create jobs, and furthered the advancement of chemical engineering techniques. In fact, it developed a chemical plant that provided 1800 jobs and used the latest technologies of the time, which are still used as a model for chemical plants today.

The ability to acquire a large number of chemists and engineers quickly was a huge contribution to the success of DuPont's nylon project.

The first nylon plant was located at Seaford, Delaware, beginning commercial production on December 15, 1939. On October 26, 1995, the Seaford plant was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society.

TRANSPARENCY

On January 1, 2012, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010 (SB 657) went into effect in California. On March 26, 2015, UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 was signed into law. These laws are designed to increase the amount of information made available by manufacturers and retailers regarding their efforts to address the issue of slavery and human trafficking. DuPont endures to operate ethically.

CONTACT DUPONT

Bow Valley Square 3, Suite 910 Canada Telephone: 403-698-8536 United Kingdom Tel: +44(0)1438-734000

DuPont Engineering Polymers Production Buenos Aires Tel: +54 11 4239-3000 Tel: (55) 57221000

LINKS & REFERENCE

https://www.dupont.com/corporate-functions/our-approach/global-challenges/food.html https://www.dupont.com/corporate-functions/our-approach/global-challenges.html https://www.dupont.com/products-and-services/plastics-polymers-resins.html https://www.dupont.com/

BUILD UP - Plastic has accumulated in five ocean hot spots called gyres, see here in this world map derived from information published by 5 Gyres. All that plastic just floating around is a huge waste of resources in a sustainable sense, where we should be aiming for a circular economy.

RECYCLING TECHNOLOGY - Autonomous river and sea cleaning machines are on the horizon with energy harvesting from nature under development in 2019 - a 12m craft planned for construction in 2020 - with filtration scheduled to be added in 2021. Collaborative research with producers and end users is welcomed.

ABS - BIOMAGNIFICATION - CANCER - CARRIER BAGS - COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING NETS HEAVY METALS - MARINE LITTER - MICROBEADS - MICRO PLASTICS - NYLON - PACKAGING - PCBS PET - PLASTICS - POLYCARBONATE - POLYSTYRENE - POLYPROPYLENE - POLYTHENE - POPS PVC - SHOES - SINGLE USE - SOUP - STRAWS - WATER

This website is provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Cleaner Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774) 2019. Solar Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom. COFL is a company without share capital.

|