|

6. CLOTHING & DOMESTIC FILTRATION

PLEASE USE OUR A-Z INDEX TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE, OR SEE HOME

|

||

CAMPAIGN FOR ZERO MICRO PLASTIC WASTE - The clothing industry and the oil companies that supply them have got a lot to answer for. Politicians have got to explain, as to why they let the retailers and fossil fuel industry get away with a practice that they knew to be harmful to marine life, and rebound to cause humans serious illness. The invention of artificial fibres for cheaper clothing, and the washing machine was and is a wonderful thing. Freeing us up to enjoy life more affordably and reducing time spent cleaning apparel; as with all labour saving devices.

WHAT

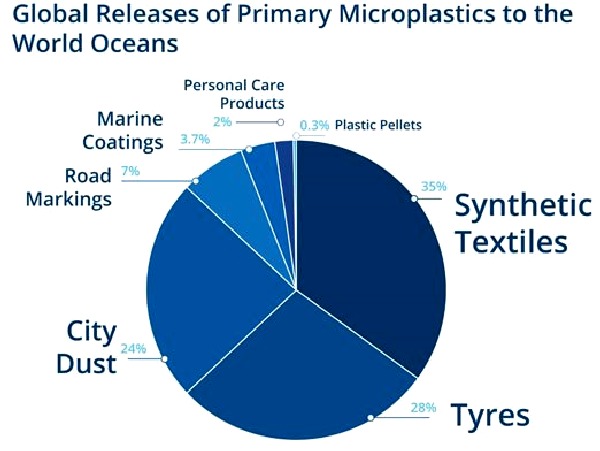

ARE MICRO PLASTICS - Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [a]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Almost all macro and microfibers find their way from domestic and industrial machines into rivers, obviously bypassing waste treatment plants that could not possibly cope with such small particles. The problem is so serious that many shellfish beds have had to be closed to human consumption, where microfibers in the guts of marine animals growing near outlets is so high.

It is not only plastic fibres causing a problem, but also cotton that is being treated such that it does not decompose like the natural plant material.

The main culprit though, is thought to be clothing made from artificial fibres such as acrylic, nylon, rayon, viscose, polyesters and so on. All plastics. The clothing is much harder wearing, comfortable, and far cheaper, but the fibers are alien to the marine environment. Even plankton at the bottom of the food chain are ingesting plastic fibers. They in turn get eaten, and so on, until the biomagnification effect bites on humans, as carcinogens and even impotency. Plastic being a carrier of cancerous toxins.

Carpets and curtains also release micro fibers into our homes, then into the air and refuse system via vacuum cleaners, even where they have cyclonic filtration.

INDESTRUCTIBLE MATERIAL - The Man in the White Suit is an Ealing Studios film from 1951 starring Alec Guinness as an inventor who creates a suit where the yarn is virtually unbreakable and does not get dirty. If only that was a possibility. Meantime, it makes sense to bridge the research gap with simple filters on machines that at the moment exhaust to the environment, free of any precautions whatsoever.

The same ethos could be applied to tyres, where the compound would not wear out, but then a reduction in tractive grip could become an obvious issue.

TEXTILES THAT DO NOT SHED FIBRES

There is a great deal of very valuable research going on into prevention of textiles from breaking up and fragmenting, so much so that there is significant resistance to putting any kind of safety net in place to remove the harmful macro and microfibres using filters in domestic machines. We can imagine that any requirement to filter waste water might present an insurmountable hurdle to the manufacturing process, even though it should perhaps be looked at. But there is nothing to prevent the makers of white goods from developing a useful break in the link between the end user who washes their clothes regularly, and the ocean.

We consider that it would be inappropriate to seek to stifle innovation that could provide an interim solution, while our chemists seek to invent a material that (effectively) lasts forever. We'll settle for longer lasting. For, if a thread never breaks down into smaller fibres, that is what we are looking at - an everlasting fabric. But, we stand ready to be corrected if that proves to be a realistic prospect. Not by supposition, but by research backed data. This brings to mind the brilliant 1951 Ealing Studios comedy film starring Alec Guinness: "The Man in the White Suit"

We do agree that textiles might be developed that are tougher and more resistant to breaking down - and that this research should continue apace, where there appears to be so many research concerns studying the subject. Any and all stones should be turned over.

It also appears that many of the micro fibres in the ocean include cotton that does not break down due to treatments when making fabrics. A sort of plasticized version of the natural plant material.

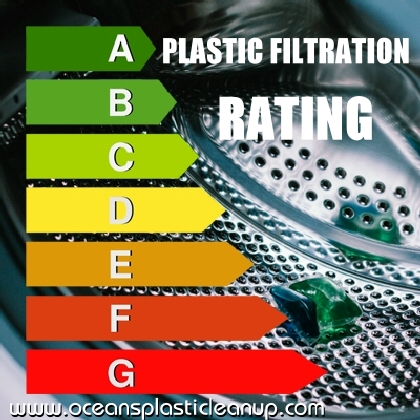

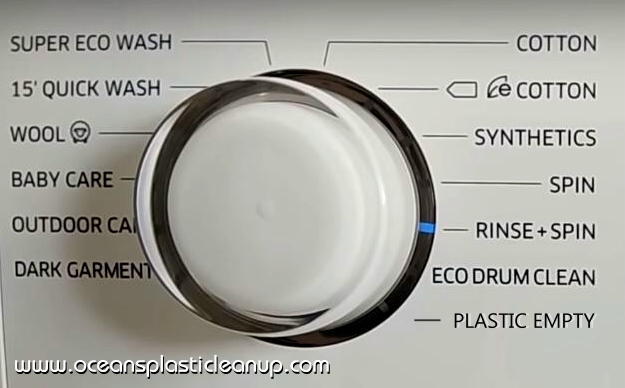

WASHING MACHINE FILTERS

A first and very simple step could be the introduction of filters on domestic washing machines, that are capable of straining out the tiny fibers, much like the mesh filter used on dryers, except that a different system would be needed to cope with much smaller fibres, such that they are easily emptied into the trash for recycling, rather than flushed down our drains during the rinse cycles - itself reliant on local authority drainage and waste treatments (or at least monitoring) being stepped up, where at the moment, their filters are not up to this particular challenge - and may prove too expensive.

Whether or not a super thread is developed in the future, it would be prudent to adopt a belt and braces approach to containing the problem. We cannot conceive that any reasonable person could object to such a proposal. It is impossible to say that an everlasting thread will not become a reality, as much as it is to say that a filter cannot be developed to catch really small fibres. That is the whole point of R&D. Keeping an open mind as to the possibilities. Regardless, filters that can contain macrofibres are used every day in clothes tumble dryers. And those macro fibres soon break down into microfibres.

This of course would pre-suppose that the textile industry would be willing to work with domestic machines manufacturers to solve one of the biggest issues of the day - and that chemists are willing to work with engineers.

We believe that much of the at present uncontrolled micro plastic waste, can be contained with a little ingenuity:

|

||

ARTICLE 6 (DRAFT)

1. Filters capable of catching macro and (as developed) micro fibers should be included on all new domestic machines (home appliances) vacuum cleaners, clothes dryers and washing machines, to include those machines in Laundromats providing clothes washing and drying services to the public, and automatic car washes.

2. Research into methods of making textile yarns that are resistant to breaking down over the course of a 5-10 year lifespan should be undertaken as a priority, with ongoing vigilance and knowledge transfer between nations, and that such genuine research should be state supported.

3. Research into producing ropes that do not fragment as quickly as polypropylene in sunlight or seawater, should be undertaken as a priority, especially as it affects fishing gear, with a view to identifying a product that more naturally breaks down in our oceans if lost at sea and is sustainable in production, or alternatively, that where more resilient strands are used, that they should be tagged as per Article 4.

4. In the search for environmentally friendly fishing gear, means of using natural fibres to replace synthetics should be ramped up, with a constant weather eye open to adapt traditional methods with new technological advances.

5. Cooperation and transparency between research organizations toward achieving either of Sections 1. 2., or 3., or a combination of 1., 2., 3 and 4., should be addressed as a matter of policy, especially where much of this work is grant funded from the public purse.

6. Research into producing rubber compounds that degrade within a realistic timescale in seawater should be encouraged and where state rules allow, grant supported, or where state rules do not allow, that policies should be altered to allow such genuine research to be grant supported to include funding independent inventors over giant corporations, where promising innovation is apparent. The same incentives being applied to Section 4., above. The aim being to develop automotive tyres that are marine friendly, as quickly and efficiently as practical.

7. Once commercially available, there should be a phased in ban on the sale of new domestic and commercial washing machines without any form of fibre filtration incorporated in the waste water discharge circuit, exhausting to external drains.

8. New washing machines with fibre filtration means, should be quickly empty-able, such that their operators are not faced with an onerous task in the regular and routine servicing of the filters. Emptying sensors and visual/audible indicators may go some way to assisting the operators in this regard.

9. Clothing should be responsibly recycled as part of local and national schemes, that authorities are required to engage with and implement.

10. Textile manufacturers should be required to to take reasonable steps to ensure that during the production process, fibres are not released into atmosphere or water courses.

11. That in all existing factories where retrospective capture equipment is installed, plastic credits should be awarded.

12. That in new factories, plastic taxes should be applied as negative credits, for failing to install plastic fibre capture filtration equipment.

13. That the same requirements should be placed on manufacturers of strand glass or optic fibres used in the manufacture of composites or telecommunications equipment.

14.

That with reference to plastic fibres and micro particles, this should include

synthetic rubber compounds used to make automotive tyres, the same incentives and

penalties being applied as if the product were plastic, with reference to

Article 7.

1.

Supermarket packaging transformation (back) to paper predominantly

|

||

This

small but nevertheless important part of the proposed clean revolution could help to

eradicate at least a good percentage of plastic and rubber sources, suggested as being a voluntary upgrade by manufacturers of white

goods, failing which legislation would need to step in to force the pace of

appliance development.

We hope by this means, that where politicians have many conflicts of interest, blinding them and making them deaf, as to the voices of the many, that such show not tell strategy, will begin to affect manufacturers as much as buyers. You will appreciate that at the moment there is very little choice for consumers, where mainstream manufacturers are not giving them that opportunity.

KEEPING UP WITH THE TIMES - A machine without an easy to empty micro fiber filter, is like an old wooden washtub in ecological terms. Make sure your new machine is ocean friendly. When washing machines were first invented - they didn't have a plastic problem. Clothes were cut from natural cloth. We're all for a return to cotton and wool, if our leaders will not regulate the system to protect marine life.

Now that France has enacted the IR microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

We need tougher MARPOL like legislation and enforcement, to prevent plastic from rivers flowing into the sea. We implore you to write to your MP, Senator, Prime Minister, President, Queen or King, to ask them to agree to introduce laws and rules that make it illegal in their countries to allow river waste (including microplastics) into territorial waters - and from there into international waters. A law like this is sure to trigger the introduction of monitoring, barriers and cleaning operations with equitable rewards for any organization providing such services. So far your leaders (except France) have demonstrated that they don't give a jot, and will not tackle the monopoly enjoyed by their political backers.

FRANCE TAKES THE LEAD - 22 MARS 2020 - ANIMAL WELFARE, CONSERVATION AND BIODIVERSITY IN THE FRENCH MEDIA

AFP reports on the last announcement made by French environmnent minister Brune Poirson before her diagnosis with COVID-19: the planned introduction of plastic microfibre filters in washing machines, making France the first country to introduce this regulation.

TREEHUGGER 2020 13 OCTOBER - REUSEABLE LAUNDRY FILTER CAPTURES 90% OF MICROFIBERS

La secrétaire d'Etat à la Transition écologique, Brune Poirson, réunit lundi les fabricants de lave-linge pour préparer l'application d'une mesure adoptée dans la loi pour l'économie circulaire: l'installation de filtres à microfibres plastiques dans les machines à laver neuves.

FASHION REVOLUTION.ORG - What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [c]: -

Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible - Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [e], coatings and pre-washing garments [a]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [f]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [h]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no

EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

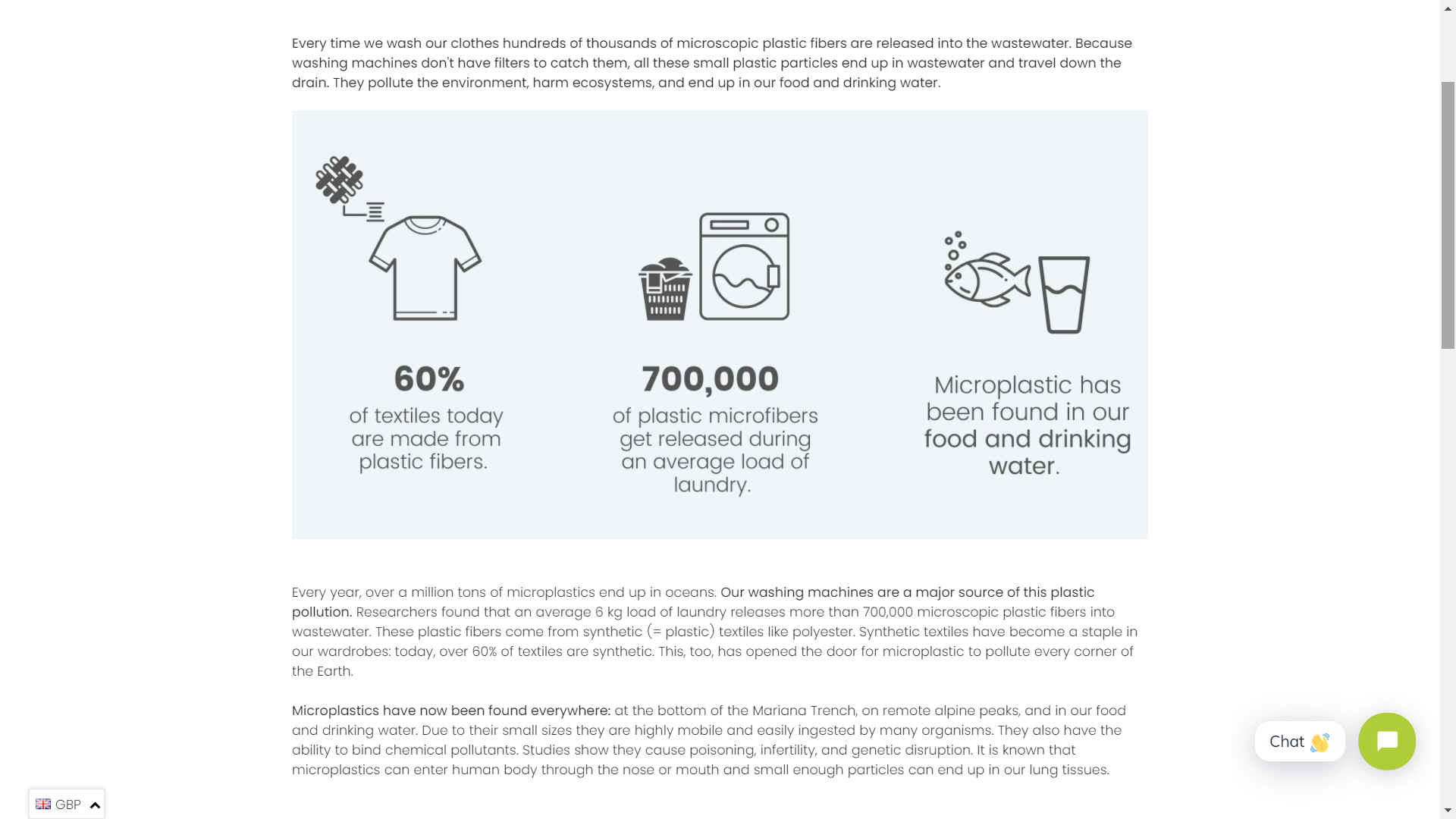

MICROPLASTICS

ARE EVERYWHERE -

Washing machines are a major source of this plastic pollution. Researchers found that an average 6 kg load of laundry releases more than 700,000 microscopic plastic fibers into wastewater. These plastic fibers come from synthetic

textiles like polyester. Synthetic textiles have become prevalent in our wardrobes. Over 60% of textiles are synthetic. This has opened the door for microplastic to pollute every corner of the Earth.

WHAT ELSE CAN YOU DO?

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [c] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [k].

GARMENT FACTS USA

More than 15 million tons of used textile waste is generated each year in the United States. The amount has doubled over the last 20 years.

In 2014, 16.2 million tons of textile waste was generated, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Of this amount, 2.62 million tons were recycled, 3.14 million tons were combusted for energy recovery, and 10.46 million tons were sent to the

landfill. For 2019, the national Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) landfill tip fee average was

$55.36/ton. Synthetic clothing may take between 20 to 200 years to

decompose.

Manufacturers should look to replace single use plastic in packaging wherever practical. Supermarkets should look for alternative packaging if it would not detract from the quality of produce or make them uncompetitive. They might support a plastic-oil circular economy with recycling depositories at their stores.

Producers of white good appliances should manufacture from recycle-able materials, indicating that such consideration has been included at the design stage, to give customers informed choices. Customers should choose their washing and drying machines with care, not to oversize - such as to save energy.

Drum (also sometimes referred to as a tub) sizes for washing machines typically range from 5kg to 12kg. The weight measurement represents the number of kilos of dry clothes the drum can hold. Normally, the larger the drum size, the better the washing machine will be at handling mountains of laundry in one go, for large families. However, big is not necessarily the best way to go. What you need to do is find a washing machine whose drum will be able to keep up with your usual load of clothes.

Many washing machines don't double up as a dryer, where stand alone dryers are

commonly more efficient, if space allows. Spinning is a better way to remove water from clothes at the end of a wash. The higher the spin speed, the more water your washing machine can draw out, which means the less time the clothes will require to

air or machine dry. Hence, fast spin speeds should be high on the list of priorities for your washing machine.

AWW SHUCKS - The invention of the washing machine was and is a wonderful thing. Freeing us up to enjoy life more, as with all labour saving devices. In the past these machines were not the all singing and dancing affairs they are today. Humans still had to help in clothes processing. Today we just select a program, push a button and walk away.

ISOLATION & VENTILATION

A laundry room should be one of the most functional and workable rooms in your home. Ideally, the area should have plenty of natural or artificial light, counter space to sort and fold clothes, secure storage for laundry products, and adequate space for all laundry equipment. Whether you are building a new home or remodeling.

INDIFFERENCE - Tangled in a societal maze and cemented by big business oligarchs, what chance does an oyster or muscle stand, let alone a turtle, where they cannot speak, write, or vote.

You can speak for them by not purchasing goods in packaged in plastic, unless it is responsibly recycled, and by fitting a filter to your domestic machines, where they empty to a sewage treatment system.

GOVERNMENT APATHY

Governments

simply don't care enough at the moment to revise their policies, because it's

cheaper to take a dump in the ocean and heaven forbid, spend money on filtration for

the sake of biodiversity.

Politicians are reeling from climate change, they know that nobody can see them

dumping waste in the oceans, and it underpins their frail economies to continue

to do so - for the sake of getting re-elected.

It's all about power, not lives. They will continue to slaughter defenseless

animals, so long as the electorate continue to do nothing. Doing nothing is the

same as agreeing with the slaughter. That is why we had World War Two, the moral

world finally had to act to stop Nazi

Germany invading and taking over the less able in Europe,

leading to concentration

camps, to eliminate political opponents and genocide

on an industrial scale. That will only change with a food crises and poisoned fish being declared carcinogenically inedible by the World Health Organization. I.e. with cancer victims falling like Covid-19 victims, taking up hospital beds. And even then that will only be because of the rising Healthcare bills. Governments actually seem to like it when elderly vulnerable patients go to the grave early. It's like ethnic cleansing, but legal. Or is it? Is it legal to engineer a situation where because human life expectancy is higher and so medical costs in later life are more of a social burden to a state, that health trusts, doctors and nurses are trained to give minimalist treatments to the elderly, so that in effect, their life expectancy is cut short - meaning that people not only die earlier, but also in considerable pain with loss of quality of life. Surely that is a form of state sanctioned murder that can only get worse if we engineer toxins into our seafood?

LINKS & REFERENCES

[a] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425 https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-53196793 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/mar/14/plastic-microfiber-pollution-clothes-washing-solutions https://www.treehugger.com/planetcare-filter-captures-microfibers-5081906 https://planetcare.org/ https://www.fashionrevolution.org/our-clothes-shed-microfibres-heres-what-we-can-do/ https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/filtres-anti-plastiques-dans-les-lave-linge-brune-poirson-reunit-les-fabricants-17-02-2020-2362973_23.php https://blogs.mediapart.fr/melextra-jet/blog/220320/france-first-introduce-microfibre-filters-washing-machines

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-53196793 https://www.treehugger.com/planetcare-filter-captures-microfibers-5081906 https://www.fashionrevolution.org/our-clothes-shed-microfibres-heres-what-we-can-do/

https://www.greenpeace.org/international/press-release/7566/black-friday-greenpeace-calls-timeout-for-fast-fashion/ https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-11/documents/2014_smmfactsheet_508.pdf https://nrcne.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/EREF-MSWLF-Tipping-Fees-2019-FINAL-revised.pdf https://www.close-the-loop.be/en/phase/3/end-of-life https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/apparel/recycled-fashion/market-potential https://www.plateconference.org/age-active-life-clothing/ https://www.fairact.org/wp-content/uploads/Wrap_Valuing_our_clothes_30pourcentsVoC_FINAL_online_2012_07_11.pdf https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-11/documents/2014_smmfactsheet_508.pdf https://www.smartasn.org/resources/frequently-asked-questions/ https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data

1.

Greenpeace. "Black Friday: Greenpeace Calls Timeout for Fast Fashion." Accessed Nov. 6, 2020.

HARBOURS - The ocean washes up a small percentage of plastic flotsam to remind us of our sins. All the beach and marina cleaning is unable to keep up with the dumping in our rivers, which ends up swirling about the seven seas.

|

||

|

PLASTIC SNACKS - Below the waves and out of sight, marine life is eating plastic like there is no tomorrow, and there may well be, if nothing is done about it. Nets are trapping and suffocating wildlife and beaches are strewn with fishing discards and plastic flotsam. Big business is responsible, but not so much as the politicians who allowed this situation to develop.

|

||

|

PLEASE USE OUR A-Z INDEX TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE

This website is provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Cleaner Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774) 2021. Solar Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom. COFL is a company without share capital whose founding objects are charitable, being not-for-profit.

|