|

2017 - According

The

Blue Danube drains some 315,000 square miles (817,000 square km) includes a variety of natural conditions that affect the origins and the regimes of its watercourses. They favour the formation of a branching, dense, deepwater river network that includes some 300 tributaries, more than 30 of which are navigable.

The river basin expands unevenly along its length. It covers about 18,000 square miles (47,000 square km) at the Inn confluence, 81,000 square miles (210,000 square km) after joining with the Drava, and 228,000 square miles (590,000 square km) below the confluences of its most affluent tributaries, the Sava and the Tisza. In the lower course the basin’s rate of growth decreases.

More than half of the entire Danube basin is drained by its right-bank tributaries, which collect their waters from the Alps and other mountain areas and contribute up to two-thirds of the total river runoff or outfall.

Romania has a very poor track record of waste management. In 2013, only 5 percent of all trash was recycled, compared to a European Union average of 28 percent. That means most of the country's waste ends up in landfills - some of them illegal.

The

European Commission has criticised how the Romanian government manages waste, and even allocated funding for new waste disposal systems. It's slowly improving - that 2013 figure is up from just 1 percent in 2010, and both private and public sectors are making an ongoing effort to improve.

But Romania is one country. Globally, most plastic waste is still ending up discarded.

Even when we do try to recycle it - a difficult and expensive process - things don't always go according to plan.

The United States is currently in a 'trash crisis' due to a new policy implemented in China last in 2018 that saw an end to plastic recycling imports. This move has also affected the disposal of recyclable plastic in other countries around the world, including Canada and Australia.

According to a study published in 2017, researchers found that, by 2015, over 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic had been produced by humans since the 1950s. Over 6.3 billion of those tons had been discarded - ending up in landfill or the natural environment, including the oceans, where it's been devastating the wildlife.

Environmental scientists have warned that, if global trends continue the way they have, there could be over 13 billion tons of plastic waste in landfill, or polluting the natural environment, by as early as 2050.

Around

ninety percent (90%) of plastics in the ocean comes from just 10 rivers.

Nine of these rivers are located in Asia and one of them borders Thailand.

The top 10 most polluted rivers in the world have one thing in common – they are located alongside large

human populations with poor waste management

(PWM) systems.

The

THE GUARDIAN NOVEMBER 2016

After barely surviving decades of pollution during the communist era, the Danube is facing new threats from microplastics, pesticides and pharma waste.

Looking out over the Danube river as it passes through central Budapest, Gabor Farkass, director of Hungarian Plastics Association, bemoans his local authority’s careless attitude to recycling . “There are some sad pictures coming out in the media, because [scientists] check the riverbed, they check inside fish and birds, and they find a load of plastic,” he says.

After barely surviving decades of heavy pollution by industries in the communist era, the ecological status of the Danube river has dramatically improved. But threats from new sources of pollution are looming on the world’s most international river, which tracks almost 1,800 miles through 10 countries and four capitals.

The river is seeing a rise in plastic waste, pesticide run off and pharmaceutical waste. But perhaps the biggest difficulty is working out exactly what and where these problems are. The last Joint Danube Survey report by International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) lists the top 20 hazardous substances to the entire river and found that just seven of them are officially reported on.

“We have a massive lack of information about what kind of pollutants industries are releasing into the Danube,” says Adam Kovacs, technical expert for pollution control at the ICPDR. He says that EU legislation is behind industrial development.

One of the newer pollution threats is microplastics, which can affect fish and fish larvae that confuse the particles with food sources. A study in Austria last year discovered that 40 tonnes of microplastics, pieces of plastic 5mm or smaller in diameter, are being transported each year through the country’s stretch of the river alone. It found that littering, wind carry and ineffective waste management are key contributors as larger plastic particles in the environment breakdown into smaller microplastics.

If the synopsis sounds bleak, that’s because it is; despite the apparent urgency there is not yet a standardised scientific methodology for measuring microplastics in environmental samples. Scientists admit they know little about the long-term impacts to the Danube, human health, or the wider natural environment.

A vast number of industries use plastics in items ranging from automotive parts, cleaning agents and cosmetics to packaging, agricultural and pharmaceutical items. “Our ministry is working with plastics manufacturers, trying to reduce their plastic output into the Danube down to zero.” says Franz Wagner, from Austria’s federal ministry of agriculture, forestry, environment and water management, which funded research into the phenomena after nets in a study on Danube fish larvae also landed lots of plastic particles.

Rudiger Baunemann, director general at PlasticsEurope, a continent-wide association for manufacturers, defends the industry, which he says is doing its best to help keep plastics out of the natural environment altogether. He says it’s unfair to put the sole blame on companies for the problem. Tackling it “needs to be a joint effort between industries, authorities, NGOs, and other stakeholders,” he says.

Farkass insists that recycling is a crucial element in tackling the scourge of plastics pollution to the Danube. Waste management facilities, especially highly effective ones, which are hugely expensive to develop, are key in tackling pollution issues, he says. Kovacs believes that future treatment plants will have an additional processing phase specifically for micro-pollutants.

Pollution from microplastics, however, is only a part of emerging threats to the river. Recent foreign investments in agriculture in downstream Danube countries, such as a $500m (Ł400m) investment in Hungary and Romania from seed giant Monsanto, are expected to increase pollution pressure over the next few years. When fertilisers reach the river, they can lead to eutrophication (a depletion of oxygen), causing algae to grow explosively, which eventually asphyxiates organisms living underneath.

Using mostly EU funds, Hungary has invested heavily in Budapest’s modern central wastewater treatment plant, which sits adjacent to the Danube shores near Rŕkóczi Bridge. The capital’s waste enters the pungent-smelling plant as brown hazardous sludge, to eventually gush out into the river as treated clear water.

But stark political and economical disparities between the richer upper and poorer lower Danube countries, often means that such infrastructure becomes less effective the further downstream you go. The 2008 economic crisis hampered an EU roadmap to improve waste facilities throughout all Danube countries.

However, there are signs of hope. Romania, one of the poorest countries along the Danube is leading a pan-European project, DANUBIUS-RI, to tackle some of the problems affecting the river. “The goal is to understand the formation, distribution and impacts of emerging pollutants from microplastics, agriculture and pharmaceuticals,” says project leader Adrian Stanica.

The region has been hamstrung by its communist past, says Ciprian Nanu, another member of the project and secretariat at European Innovation Partnership on Water, and this has traditionally made it hard to engage with business. But he is trying to pull together business, NGOs and other organisations to overcome this. “We have to start now to build business relations in order to introduce innovation in regional markets.”

The project is looking to engage innovative water tech businesses, similar to WatchFrog, which is developing technologies to measure and monitor a range of micro-pollutants in waterways.

By Stephen McGrath

Every

year the world, produces 300 million tonnes of plastics, and 8.8 million tonnes of these are dumped into the oceans. That’s about 40 billion plastic

bottles, 100 billion single-use plastic bags, and 522 million personal care items.

If

you know a seriously polluted river, or one that should be a candidate on a

bigger list, please contact Cleaner

Ocean Foundation.

The

rivers noted, added to hundreds of other lesser contributors feed the five

ocean gyres.

1.

North Atlantic Gyre 2.

South Atlantic Gyre 3.

Indian Ocean Gyre 4.

North Pacific Gyre 5.

South Pacific Gyre

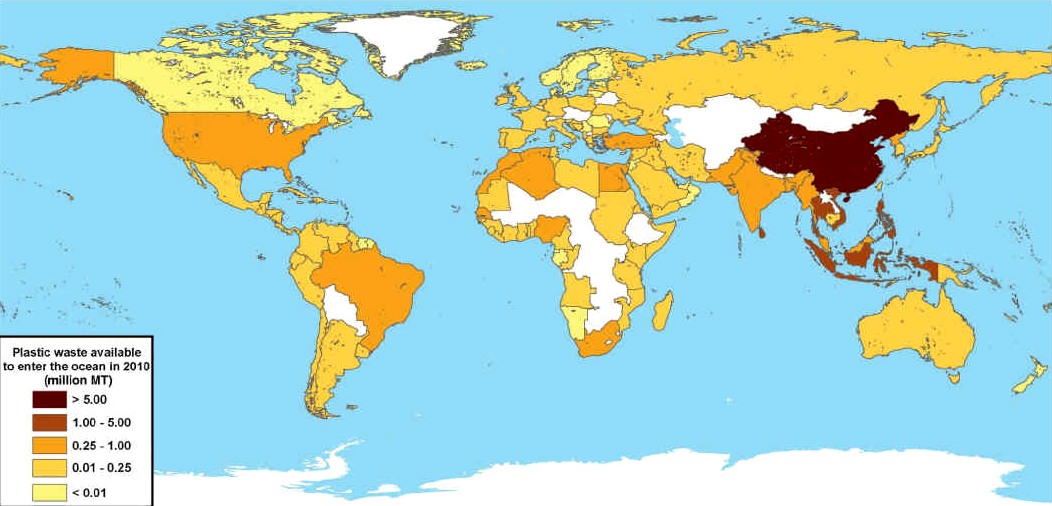

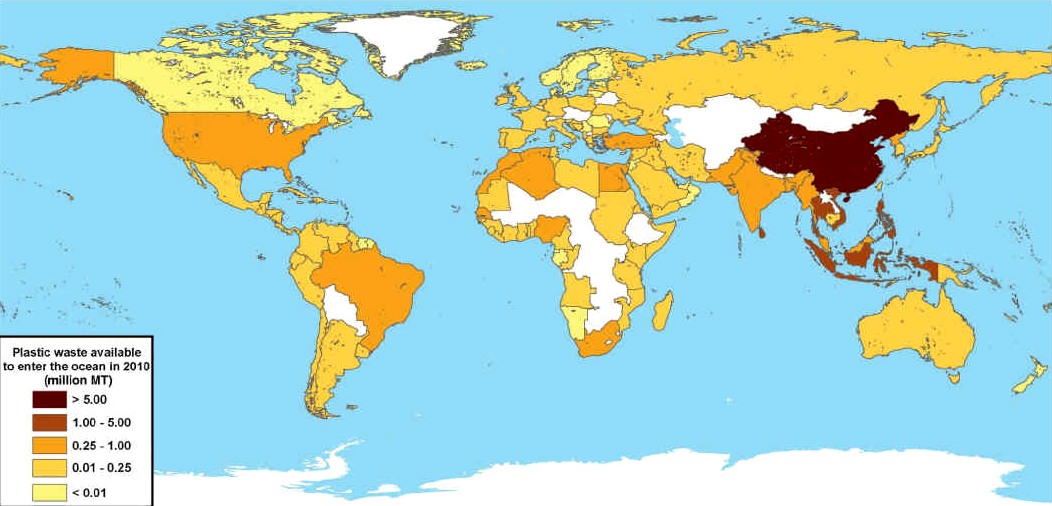

JAMBECK

2010 - Global map with each country shaded according to the estimated mass of mismanaged plastic waste [millions ofmetric tons (MT)] generated in 2010 by populations living within 50 km of the coast. 192 countries were considered. Countries not included in the study are shaded white.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/nov/13/danube-looming-pollution-threats-worlds-most-international-river-microplastics-fertiliser

|