|

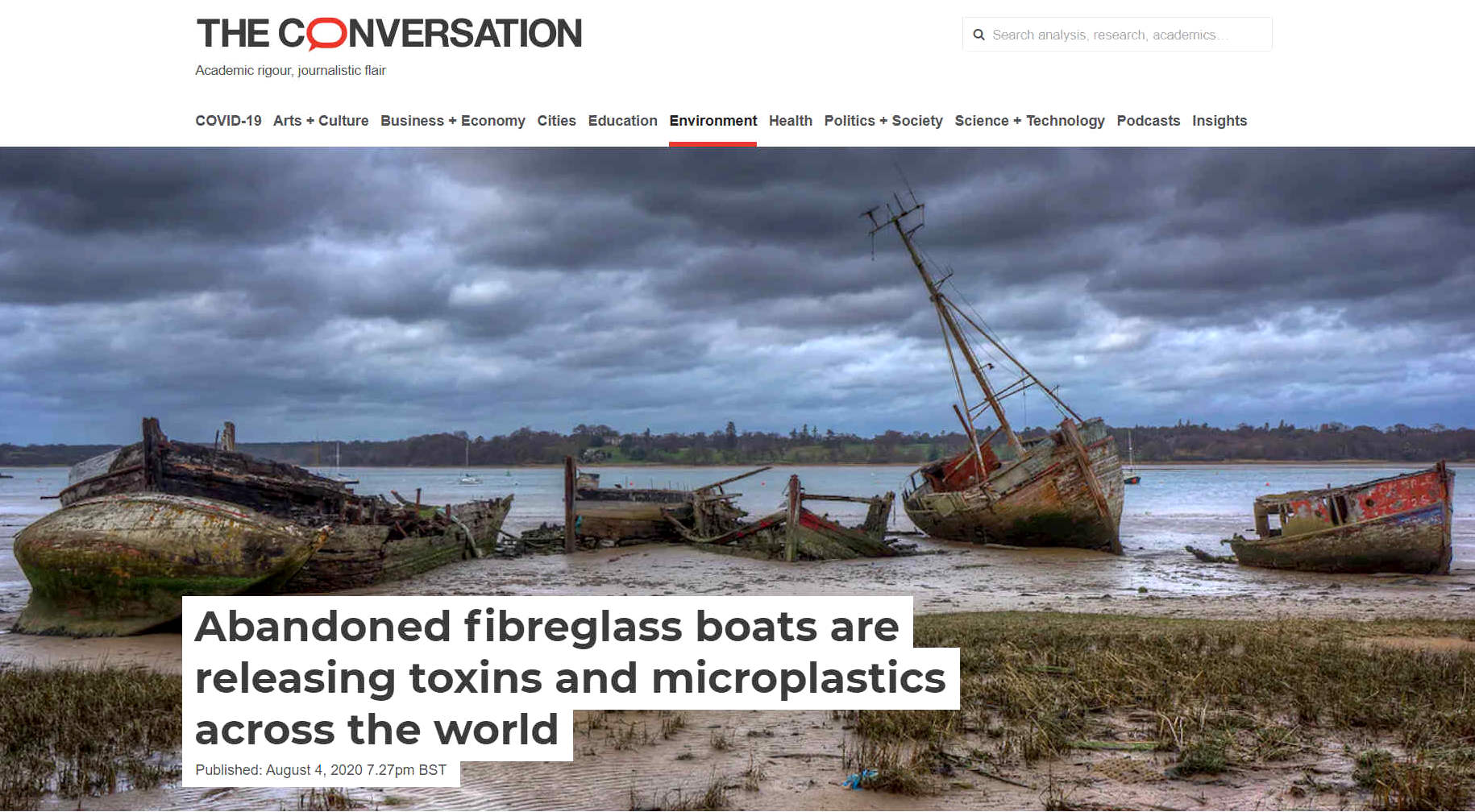

We've

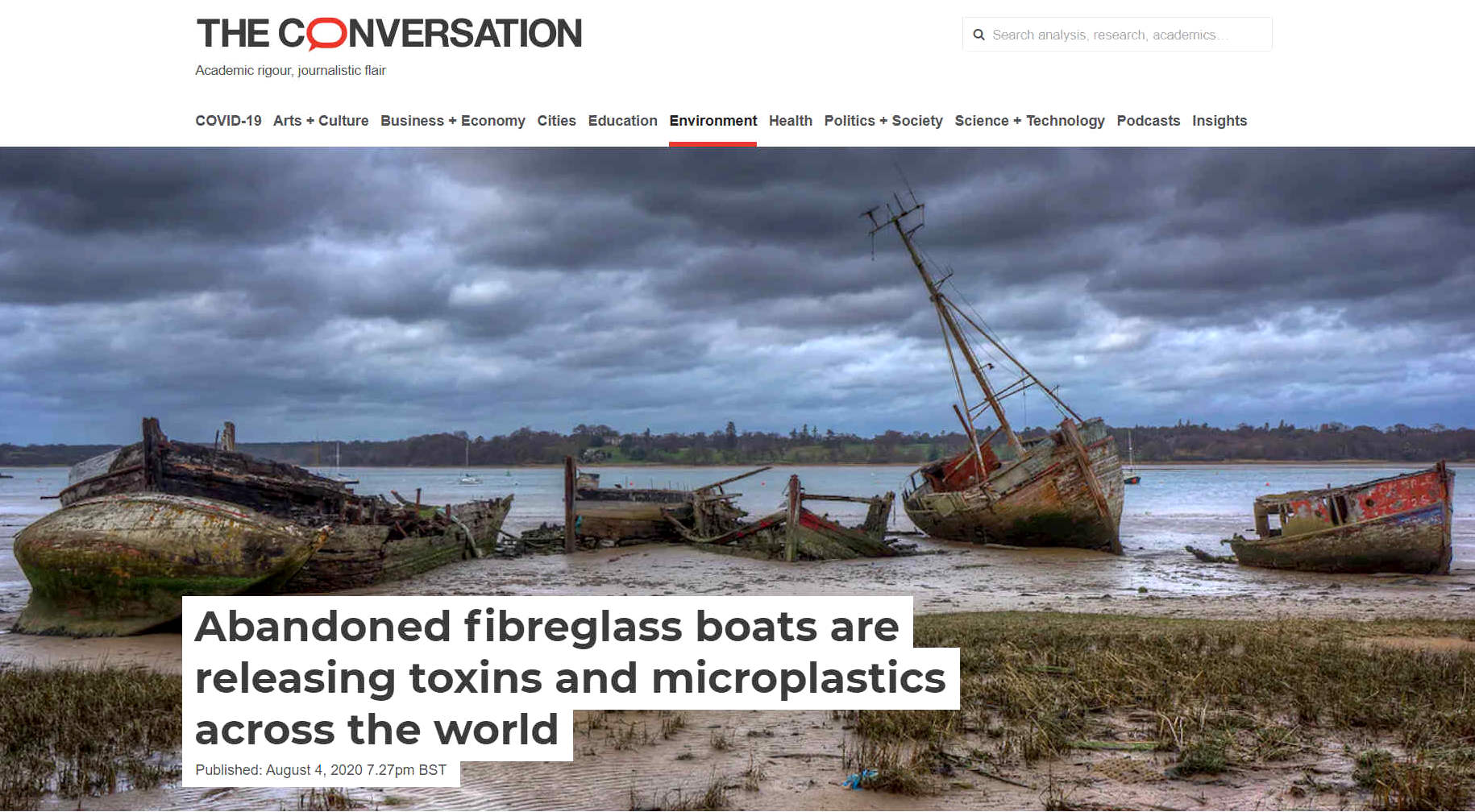

all seen scenes like this, giving rivers and estuaries a certain rustic

charm. But in a modern world conscious of toxins and responsible recycling,

abandoned boats should be disposed of more thoughtfully. Some ships like the

Elizabeth

Swann, have been

designed from the outset to be clean in operation, and clean at the end of a

long productive life.

PRACTICAL

BOAT OWNER 20 JULY 2022 - FIRST EVIDENCE OF GRP BOATS' "CANCEROUS" IMPACT ON AQUATIC LIFE

Microscopic analysis of oysters, mussels and sediment from Chichester Harbour has uncovered a dizzying number of glass fibres linked back to boatyards and derelict vessels.

The ‘really worrying’ findings by University of Brighton researchers who undertook studies off the coast of Hampshire and West Sussex have worldwide implications, yet there is no practical solution for recycling fibreglass boats in sight, with a boom in boating, plus increasing numbers of early glass reinforced plastic (GRP) vessels reaching end of life.

Dr Corina Ciocan, Principal Lecturer in Marine Biology at the School of Applied Sciences at the University of Brighton, told PBO it took a lot of detective work to discover exactly what they had found.

Embedded in oysters and other aquatic life, the shards were found as part of an initial study focused on microplastics, and are 10 times thinner than human hair.

She said: “We were looking at contamination of plastic in the water, in the sediment and in the oysters. In the oysters we found many, many strands we couldn’t explain, no one had reported it before.

“The oysters had been collected from in front of a boatyard, and we found ‘e-type glass’ which is mostly used in composite materials. The dimension of the strands corresponded to tiny fragments that usually relate to cutting reinforced glass plastic material in boatyards.

“It was like uncovering the tip of the iceberg, because nobody had published anything like this before – we were opening Pandora’s Box.”

It is believed that the fibreglass is causing ‘asbestos-like’ damage to organisms such as oysters and

mussels.

Dr Ciocan said: “The work done in boatyards and the degradation of old boats have a massive impact on aquatic mammals, water fleas and mussels.”

DR

CORINA CIOCAN - On the 2nd October 2021, Dr Ciocan gave a superb presentation on the dangers of Glass

Reinforced Plastic (GRP) boat hulls. The audience in Hastings were shocked to see

pictures of old fiberglass boats littering rivers and estuaries. And of

course sunken vessels. The fact that shellfish and other marine life are

ingesting glass micro fibres, as a result of the boat-building industry

being relatively unregulated, is something that should be rectified. It was

suggested that boats and yachts made of composite materials should have

passports, such that their working life is monitored, and they are finally

retired for destruction and where possible, recycling. Just as importantly,

boatyards should be inspected for unauthorized discharges during the

manufacturing process. Corina's work at Chichester harbour is well known,

more or less a benchmark study, where other studies around the world have

found similar results. Sometimes leading to shellfish beds being declared

unfit for human consumption. Well done to the lecturer for giving her time

to share this information with UNA supporters, and her persistence, where it

appears policy makers may not be up to speed as to the harm leisure

activities are causing. These are our views, not that of the speaker. The

Foundation are of the view that if reliable monitoring and regulation is not

implemented, that an outright ban of GRP as a boatbuilding material, should

be introduced.

CANCEROUS EFFECT

Marine biologist Dr Ciocan’s expertise is in functional ecotoxicology, focusing on biological responses of marine organisms to environmental stressors.

“My opinion, which is backed by my esteemed chemist colleagues, is that it has the attributes of asbestos – that upon entering the organism, it severs the flesh and becomes embedded. The organism develops inflammation, tumours and cancers.

“Boat abandonment and a lack of legislation for end-of-life boats and the lack of a recycling solution are all attributed – there is no environmentally friendly way of disposing of it.”

The specialist team of University of Brighton researchers started their collaboration with Chichester Harbour Conservancy four years ago, prompted by concerns about microplastic pollution in the harbour.

Dr Ciocan said: “They wanted to know ‘What are the levels and where do they come from’ – sewage effluent or the tide?

“One of the particular concerns was related to the native oyster and pollution in the harbour, which was a very successful oyster fishery for centuries, able to support about 40 fishing boats until 2018 when the fishery was closed by the Sussex Inshore

Fisheries and Conservation Authority due to the low number of oysters.”

Following the success of the Chichester Harbour Microplastics Symposium, further studies are now looking at two components from fibreglass:

The plastic component “which is nasty in itself and has a huge impact on the reproduction in animals and humans and adds to the microplastic problem in general”. Glassfibre is heavier in water, drops straight into sediment and is accessible to all organisms inhabiting the sediment.

Dr Ciocan said: “Our next study will look at crabs,

lobsters and worms. The main concern is worms keep the sediment alive and make saltmarshes grow, without worms it’s pure mud that will wash away in waves and currents. In Chichester 2.5 hectares of saltmarshes are lost every year, fibreglass might be contributing massively to this – saltmarshes are natural flood defences.

LONG LASTING CONTAMINANT

Dr Ciocan added: “Fibreglass does not degrade, we have boatyards that have been in place for decades across the world, creating this massive contamination of tiny shards of fibreglass. And where dredging occurs and the sediment is dumped out at sea, it moves the problem there too.

“We’ve had a call for collaboration with our colleagues at the University of

Portsmouth, who have been approached by lobster fishermen who have observed higher mortality rates in lobsters. After a catch, they die within 10 minutes, which is clearly a respiratory problem.

“People are getting worried that this contaminant is here to stay as we don’t have a solution for this. It’s worrying really, the boating industry is having a boom, everybody who can afford to is really keen to go out on the water, there is so much technology, so many gizmos put on a boat, the actual composite material is getting thinner and thinner.

“There’s a high turnover of boats on the water.”

£1.9M FOLLOW UP STUDY TO LOOK AT 'HUMAN HEALTH ASPECT’

Following the success of the Chichester Harbour Microplastics Symposium back in 2018, Dr Corina Ciocan is now leading a team of specialists interested in developing quick tests to detect the impact of several chemical pollutants on marine organisms, with applicability in Chichester Harbour.

The £1.9million study is financed by the EU Interreg Channel programme and is bringing together specialists from France and the UK (including Chichester Harbour Conservancy).

The Interreg RedPol project, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, focuses on the endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) – pollutants able to induce reproductive, developmental and behavioural problems in the population of wild animals (and flora), which can generate an environmental imbalance.

In estuaries and coastal areas, where EDCs can limit the production of fish and molluscs, these compounds impact environmental health as well as the associated economic activities.

The RedPol specialists will test at least six compounds suspected of significantly impacting human health and environments. The research aims to improve industry practices, consolidate regulatory assessments and promote environmentally responsible behaviour.

Harbour Master Richard Craven, of Chichester Harbour Conservancy, said: “It is of great importance to the users of Chichester Harbour that we understand the sources and impacts of pollution in Chichester Harbour, and take early steps to tackle them. Our collaboration with the University of Brighton is providing a forensic assessment of the health of the Harbour.”

‘TIDAL WAVE OF BOAT

ABANDONMENTS’

Hampshire-based Boatbreakers is one of the few UK firms specialising in the disposal and recycling of end of life boats. Spokesman Luke Edney believes there could be a “tidal wave of abandonments” in the next 15 years.

He told PBO: “The reason I say a tidal wave is because boats started being made from fibreglass in the 1960s, those are now naturally getting a bit long in the tooth and losing value.

“Then you’ve got the 1970s, 80s, 90s and 00s boats getting older and losing their value. As fibreglass technology improved over the years, it was made thinner, some of the younger boats are not as tough as the older ones.

“Some places are developing technology to change that, and I’m sure there are places that would try and take a boat apart but it’s a costly process. In real terms landfill is the only option at the moment.

“I really hope that changes in the future but I also hope they don’t ban fibreglass going into landfill without real alternatives being in place, as it would increase the number of old boats being abandoned.”

There is concern that owners could take boats out to sea, drilling holes and letting them sink, if disposal routes are not created through legislation. Paddleboards and surfboards containing fibreglass are also currently unrecyclable and could pose a danger to marine life if dumped.

SCRAPPAGE COSTS

End-of-life vehicle regulations mean people may get £50 for scrapping a car – but Mr Edney said getting rid of a boat can cost about £100 per foot, meaning £3,000 for a 30ft (9m) vessel.

The BBC reports that Truro Harbour Authority in Cornwall spent £75,000 disposing of an old fishing boat and £50,000 getting rid of another. Mr Edney added: “Boats put such a pressure on finance, you’ve got to keep it somewhere. If a 30ft boat is costing money each year, people get a bit desperate to get rid of it.

“We sometimes get asked by boat owners to get rid of a boat, due to money trouble, it might be a really nice project boat but it needs a new owner, we’ll post it on our ‘Boat Scrapyard’ group on Facebook and say ‘open to sensible offers.’ I set it up in lockdown when I was furloughed and it’s got 37,000 members.

“People post every day. “If it’s a ropey boat we don’t sell it. We would strip off any items such as engines, outboards, lifejackets, rope,

anchors and post those on our boatscrapyard.com shop – it’s like an online boat jumble. We would also recycle as much as we can – metal and wood.”

At Boatbreakers, the process for dealing with end of life boats is to crush the fibreglass “as small as possible”, then that goes into landfill.

Luke added: “It’s the lesser of two evils. If it’s abandoned, the boat will break down and microplastics get lodged in mussels and seafood. If you’re eating locally sourced mussels, then you’re eating the boats, which is not a nice thought that I’m eating fibreglass.”

"AN ISSUE NOT JUST ON OUR SHORES"

A Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) spokesperson said: “Illegal disposal of recreational boats is an issue not just on our shores, but in the whole North-East Atlantic.

“The UK is leading action under the new Regional Action Plan on Marine Litter to tackle end-of-life vessels. Working together with other countries, we will map the scale of the issue across the region and develop guidance to improve waste management for recreational vessels that are no longer wanted or fit for use.”

“The second Regional Action Plan on Marine Litter (RAP-ML) under OSPAR, the Convention for the Protection of the North East Atlantic, was launched on 28 June at the 2022 UN Ocean Conference. The RAP-ML serves as the main instrument to prevent and reduce marine litter as part of the North East

Atlantic Environment Strategy 2030.

“Under the RAP-ML, we are taking leadership on improving the management of end-of-life recreational vessels. The UK is taking concrete steps to map the scale of the issue of end-of-life recreational vessels not only along our coastlines, but across the whole North-East Atlantic region, with the aim of then developing guidance to support better vessel waste management in the future.

“The UK also works internationally with other contracting parties to the London Convention and London Protocol to prevent dumping of waste and other matter at sea, including on improvements in end-of-life management of fibre-reinforced plastic vessels.

“The UK has established a £500million Blue Planet Fund, launched by the Prime Minister on 12 June 2021 at the

G7 Summit. The fund will support developing countries to protect the marine environment and reduce poverty.

“The UK is an active member of the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI): a pioneering alliance of the fishing industry, private companies, NGOs and governments working to solve the global problem of abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear.

“The UK Government is working with the Devolved Administrations to tackle waste fishing gear containing plastic in UK waters.

BID TO TACKLE COMPOSITES RECYCLING CHALLENGE

A new consortium has been formed with a long-term aim of creating the UK’s first glass fibre composites recycling and re-use facility of its kind.

Made up of the UK’s leading marine and maritime companies, composites specialists, academic institutions and local government organisations, the ‘Blue Composites Project’ aims to break ground in composites recycling and re-use to address the key environmental challenges facing the UK’s marine industry in its transition to

zero emission shipping by 2050.

The collaboration is led by Blue Parameters, a Guernsey based marine consultancy, with the aim of creating the UK’s first large-scale glass-reinforced plastics (GRP) and fibre-reinforced plastics (FRP) recycling facility that will not only look at the process of recycling composite materials but also how the reclaimed materials and fibres could be repurposed for use in new composite components, such as boats, caravans, wind turbine blades and other high-performing products.

GRP BOAT STATISTICS

There are an estimated six million boats in the EU alone, 95% of which are made of GRP.

Every year, around 1-2% (60,000-120,000) of these boats reach the end of their useful life. Of these, only 2,000 are recycled, while 6,000-9,000 are abandoned. Recycling old boats is an expensive business, costing an estimated €800 (£706) for a 7m (23ft) boat, rising to €1,500 (£1,324) for 10-12m (33-39ft) and up to €15,000 (£13,243) for boats over 15m (50ft) long.

According to the International Marine Organisation (2017), around 55,000 tonnes of GRP waste is produced from the UK marine sector every year, with the level expected to increase by 10% per year.

'REVOLUTIONARY' DEECOM PROCESS

The National Composites Centre has recently completed a project with B&M Longworth and Cygnet Texkemp that successfully reclaimed continuous carbon fibres from a whole pressure vessel using the DEECOM process and re-used them to manufacture a new pressure vessel. This was the first time this process was achieved in the UK.

Originally designed to remove waste polymer from plastics filters and production equipment, the DEECOM process, developed by B&M Longworth, uses pressurised superheated steam, to penetrate microscopic fissures in the composite’s polymer.

Upon decompression, it expands, cracking the polymer and carrying away broken particles. This pressure swing cycle is then repeated until all the matrix (the material suspended in the polymer) has been separated from the fibre, allowing the monomers to also be reclaimed for possible reprocessing.

It essentially ‘cleans’ the fibre, leaving the primary component material intact and undamaged, allowing for any length to be retained undamaged, providing much more scope for the material to be re-used in a wider range of applications.

Jen Hill, director at B&M Longworth, said: “We’ve been calling for a long time for this multi-disciplined approach to tackling FRP waste and we really believe that the impressive line-up of partners and supporters within this consortium are the right people to make it happen.”

PROFESSIONAL BOATBUILDER 25 JANUARY 2021 - FIBREGLASS DISPOSAL

The problem of sensible and effective fiberglass disposal is well documented, and proven technological and regulatory solutions are available. So why does practical end-of-life disposal for old composite boats remain elusive?

It’s 2021 and we are still trying to figure out how to best deal with derelict fiberglass boats. In the United States and many other countries, the immediately practical answer is to chop them up and cart them to the landfill despite the considerable recyclable material in each boat. It’s like those clear polyethylene terephthalate (PET or PETE) boxes that protect our prewashed greens; the technology exists to recycle them and they are labeled as such, but when the arugula is gone, in most jurisdictions there’s no market for the material, so they’re simply cut up and trashed. Plastic can be fantastic, but when it comes to end-of-life processing, not so much.

Rereading Eric Sponberg’s prescient 1999 article about this very topic, “Recycling Dead Boats” (Professional BoatBuilder No. 60), it is disappointing that despite grand promises and clever ideas, not much has changed. Old glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) hulls keep piling up in harbors, backyards, boatyards, and landfills, perhaps because the central issues are stubborn: Fiberglass laminates are long-lasting, difficult to disassemble, and have scant value as recovered material. There’s no happy second coming for GRP like there is for steel, aluminum, glass, or paper, which are part of an established recycling industry that turns old material (e.g., beer bottles, soda cans, and shipping boxes) into new products. In practice, none of these cycles is completely self-sustaining, often requiring the addition of virgin material with each use cycle.

It’s possible to reuse or downcycle fiberglass composites by grinding them up, burning the attached resin as fuel, or using the ground laminate or reclaimed fiber as filler material. None of the processes is highly profitable, which means the best hope for old GRP boats is to separate materials like metals and wood for scrap. The old fiberglass hulls were designed and built for durability, not reuse. By and large, the life of a fiberglass boat remains a linear affair, starting with the extraction of the crude oil that’s refined into the materials used to build it. Decades later, those petroleum-based products invariably end up in the dump or abandoned. When left in a creek, bay, or marina, derelict boats become environmental hazards. The basic formula behind this regrettable trend is best expressed as:

Resale Value < Cost of Proper Disposal = Abandonment

With fines little more than a slap on the wrist, there’s no effective deterrent to abandonment. In the U.S. alone, thousands of unwanted boats clutter and pollute public waterways. It could be a different story if boats, like cars, were subjected to inspections to ensure their soundness, and aging craft were tracked, so they could be decommissioned and taken out of circulation before they become a leaky reservoir of toxic substances. But even if such a policy were adopted, it still wouldn’t address the cost of responsible disposal.

SEARCHING FOR ECONOMIC VIABILITY

Following discussion of end-of-life management of fiberglass boats as part of the London Convention and London Protocol in 2016, the

International Maritime Organization

(IMO) commissioned a study to review options for boat disposal and recycling with special focus on small island developing states (SIDS) with limited resources and disposal options. It published its findings in a 2019 report called “End-of-Life Management of Fibre Reinforced Plastic Vessels: Alternatives to At Sea Disposal.”

Over the years, work in this field includes multiple reports concluding that, at present, there is no viable financial market for the resulting material, because it is not especially useful or valuable.

Hence, the most common disposal strategy in most countries, including the U.S., has been the landfill. Only where regulatory pressure prohibits this practice are other solutions being developed and implemented. “Whilst financially viable options are currently limited, the market is being developed with crushed FRP material being used in…concrete, tarmac, and also as filler for other FRP items,” the IMO report states. “The market is well intentioned, though as a cost model appears to have limited application.” Technical solutions for recovering fibers and resin exist—pyrolysis, where material is burned to recover fibers for reuse (resins are lost in combustion), and solvolysis, where chemical replacement releases resins and fibers—but as the IMO notes, “These processes are expensive and not fully commercially viable at present.” As we shall see in Part 2 of this series, efforts are under way to find solutions and scale them to make them economical. Money, as usual, is the sticking point: Who’s picking up the tab? Right now, it’s taxpayers. While the profits of building new boats remain private, the cost of cleaning up end-of-life boats is socialized. But in some places, that’s changing. In France, for instance, industry shares the burden by assuming end-of-life responsibility for boats by financing a nonprofit to remove, dismantle, and dispose of old fiberglass boats, a process also supported by an environmental tax.

[Horay for common sense]

DROWNING IN FIBERGLASS

The growing problem of fiberglass disposal goes far beyond the boatbuilding industry and has global implications. In the U.S., GRP demand rose by 1.7% in 2019 to 2.6 billion lbs (1.18 million t), according to the “2020 State-of-the-Industry Report,” published in Composites Manufacturing Magazine. That is expected to climb to 3 billion lbs (1.367 million t) by 2025, pending adjustments for the effects of COVID-19. After six consecutive years of growth in GRP production, European demand flattened to 1.141 million t (2.5 billion lbs) in 2019, according to a report published by AVK, the German Federation of Reinforced Plastics. GRP accounts for well over 90% of reinforced plastics/composites production, with two-thirds destined for the transport and construction industries, followed by sporting/leisure goods and the electric/electronics industry, each with approximately 15% of market share.

These numbers pale in comparison to China’s GRP production, which in recent years exceeded 60% of the world’s total output, according to Ray Liang, PhD, director and chief scientist of the i-Center for Composites. Annual production capacity in China exceeded 5.5 million metric tons (12 billion lbs) for the past several years, but composite shipments in 2018 declined 3.15% to 4.3 million metric tons (9.5 billion lbs). They fell another 8.5% from January through September 2019, largely because the government imposed tighter regulations, as Liang reported, to promote innovation, productivity, waste reduction, and more efficient management. They forced many producers to close shop.

I asked John McKnight, Senior Vice President, Environmental Health and Safety at the National Marine Manufacturers Association (NMMA), what plans and initiatives exist in the U.S. to address GRP boat disposal. We talked about old boats abandoned because owners die, or people with grand dreams of buying boats to fix them up fall short. McKnight: “Problem is, marinas and boatyards get stuck with all these derelict boats, and they can’t do anything with them unless they have title. The top priority is putting together a mechanism…to change the law.” (For information on rebuilding titles, see Reuel Parker’s Rebuilding Titles: 5 Steps.)

We discussed the regulatory restrictions of Europe that made disposal of fiberglass in the landfill illegal in some countries and spurred alternative approaches and solutions. And we touched on funding, or the lack thereof, for agencies tasked with collecting derelict and abandoned boats, cleaning them up, and turning them over to a processor. Among boatbuilders and the broader composites manufacturing industry, it seems there’s plenty of awareness of the problem but not yet a sense of urgency to systematically fix it. “The American Composite Manufacturers Association contacted me a while back and asked the same questions about addressing the recycling of fiberglass,” McKnight said. “They are thinking about it, and we are too, but it hasn’t been on the top of our agenda.”

ROGUES

GALLERY - They are everywhere. And, for some reason we just walk on by, as

if it was perfectly natural. And that is because in the good old days,

abandoned wooden boats did no harm to the environment. We got so used to

seeing wooden boats and steel wrecks that are relatively harmless

ecologically, that we were lulled into a false sense of security. The

thousands of old vessels littering our rivers and harbours, must be seen for

what they are. Potentially cancerous pollutants, that politicians in the UK

appear to be ignoring. When what we need is statute. New laws to protect our

underwater

kingdom.

YOU'RE ALWAYS WELCOME AT THE DUMP

“Surprisingly, landfills are not the worst place to send fiberglass, since most of them are vault types, which are not supposed to leach,” explained Aaron Barnett from the Washington State Sea Grant, an organization that helps fund that state’s efforts to remove derelict vessels from the environment.

Just how many legacy boats are derelict and need to be dealt with is not easy to determine. In 2019, prior to the recent COVID-induced boat-buying boom, there were approximately 11.88 million recreational vessels registered in the U.S., according to recreational boating statistics, one million fewer than at the peak, in 2007. How many of that one million are derelict is difficult to say. According to the Rhode Island Marine Trades Association (RIMTA), “Between 2003 and 2012 an estimated 1.5 million recreational craft were retired in the U.S…. This rate of disposal is not expected to slow down, as many first-generation fiberglass boats (launched 1970s–90s) have begun to reach their end-of-life status.” Running with this estimate and assuming that a similar number of boats might have reached retirement age since 2012, we’d be looking at approximately 3 million end-of-life boats in the U.S. in the past 20 years.

I called a couple of landfills around Portland, Oregon, about discarding a (fictitious) 20‘ (6.1m) fiberglass vessel. Within five minutes I had all the information I needed and got a lesson in American efficiency and customer service. No surprise, because trash is big business, generating revenues that grew from $39.4 billion in 2000 to $63.4 billion in 2017 and are forecast to reach $81 billion by 2023. “Come by. We take boats all the time,” a friendly attendant at a transfer station advised. “There’s a fee of $150 for the demolition and then it’s $123.95 for the first 2,000 lbs of boat weight.” The Metro dump had some size restrictions. “It goes with the regular garbage, so you have to cut it in half or chop off the ends to make it fit into our compactor, which can take only pieces up to 12‘ in length,” another attendant informed me. Cost is $28 for the first 360 lbs, then $98 for every additional ton. What about engine, oil, and other fluids? “You would have to remove that. Motor is free, because it’s metal, but you need to take the fluids to hazardous waste. We’re here 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., seven days a week.” Any concerns about problems that fiberglass might cause in the landfill? No, none.

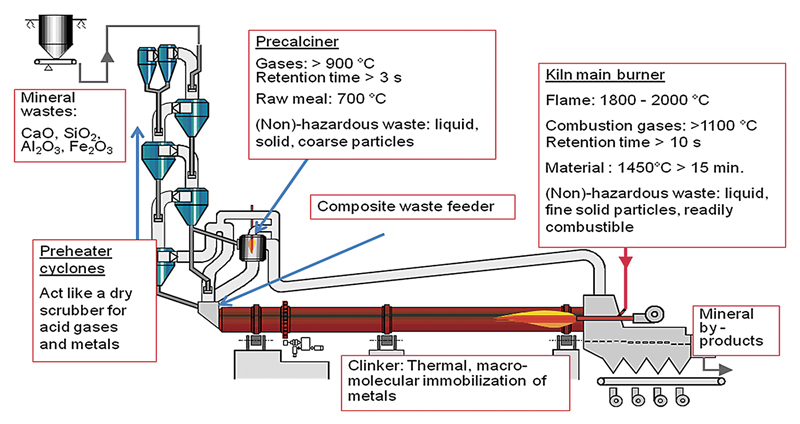

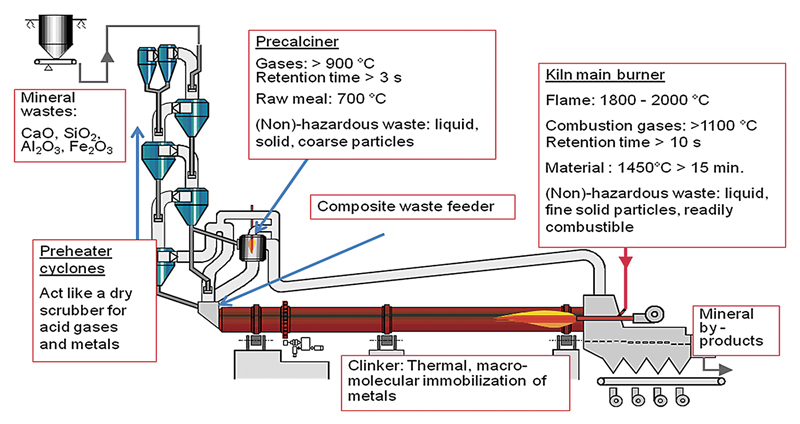

THE COPROCESSING ALTERNATIVE

That doesn’t mean there’s no role for methods and processes that help get rid of fiberglass waste while also yielding environmental benefits. One is cement-kiln coprocessing, where ground-up fiberglass waste helps reduce the carbon footprint of the cement industry. Coprocessing has been in use in Europe, where the wind industry is big and the landfills are small, and GRP waste would be piling up sky-high.

“In my mind the best benefit is to air quality,” Barnett said. “When cement kilns use an alternative fuel as opposed to tires and other petroleum products, net CO2 emissions are reduced dramatically.” The European Composites Industry Association (EUCIA) explains: “By using composite regrind in coprocessing, a significant reduction of CO2 emission of the clinker manufacturing process can be obtained. Depending on the quantity of composite regrind included and the specific cement plant technology, the reduction can be as high as 16%.”

In 2016, when researching their best course of action for a program called Rhode Island Fiberglass Vessel Recycling (RIFVR), Rhode Island Sea Grant and RIMTA consulted with several European outfits that develop waste management solutions for decommissioned wind-turbine-rotor blades and other plastic and GRP products such as pultrusion profiles, tanks, pipes, circuit boards, truck spoilers, sinks, cable ducts, and boxes.

In 2019 RIMTA and the 501(c)3 RIMTA Foundation completed the first phase of a pilot project that examined and verified the viability of cement-kiln coprocessing for end-of-life fiberglass boat hull material. Partners included 111th Hour Racing, Association of Marina Industries, BoatU.S. Foundation, Brunswick Marine, Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corp., Rhode Island Dept. of Environmental Management, J.R. Vinagro Corp. (waste management service), Geocycle/LafargeHolcim Cement (kiln coprocessing), and a handful of boatyards. As the NMMA’s McKnight pointed out, the yards have had to deal with abandoned derelict boats clogging marina slips while running up the tab in unpaid fees and taxes.

In the RIMTA pilot, six boatyards contributed 22 boats of varying sizes and types from across Rhode Island. Before shipping them to Vinagro’s facility, the yards removed metals, oils, fuel, and batteries and recovered valued components such as engines and rigging. Next, the hulks were cut up and crushed by heavy machinery and fed into a horizontal grinder. “We process that material down to a 2“ [50mm] mixture for use by the cement industry,” RIMTA’s project director, Evan Ridley, said.

Material consistency and volume are critical to quality control in industrial production. It’s no different in coprocessing, so approved materials are blended with others to ensure the desired consistency. Given the diversity in fiberglass composite hulls going into the grinder, this step makes sense. Ridley: “That mixture sometimes maybe contains [only] 40% fiberglass, while the rest of it is balsa wood or foam core or other ancillary components of hull construction…. Early on we went through a pretty thorough laboratory analysis process with one of our partners to determine that stuff…in that mixture wasn’t going to cause any red flags from a [alternative material] value standpoint.” The ground-up fibers were loaded into an open trailer, which made the 900-mile trip to the Geocycle facility in Dorchester, South Carolina, where it was blended with other nonhazardous components from a variety of sources to be used as fuel for LafargeHolcim’s cement kiln in Holly Hill, South Carolina.

“Alternative fuels replace coal, petroleum coke, and natural gas, which are common sources for heating process cement kilns. To utilize them, the facility needs approval from state and local permitting authorities and a feed system to introduce the materials into the kilns,” said Kelly Brown, a spokeswoman of LafargeHolcim. “The next step is to evaluate the fuels for acceptance, not only with the permits but also [for] our cement manufacturing process. Most regulatory constraints are around the requirements as a fuel, such as how it will be handled while on-site and also other limits, such as heat value.” The caloric value of the blend has to approximate that of the traditional coal mix it replaces, Brown explained. “So keeping the heat value in that same range of ~11,000 British thermal units [Btu]/lb or more is preferred. To ensure good combustion, and meet our regulatory permitting, the material must [offer] greater than 5,000 Btu/lb.”

Lastly, who pays for coprocessing: the waste/fuel supplier or the cement manufacturer? “There are a lot of equipment, operational, and regulatory requirements as well as data collection and documentation systems to handle alternative materials,” Brown noted. “Because of this, we must charge the supplier for this green solution.”

Here’s how cement-kiln coprocessing works. In cement manufacturing, raw materials such as limestone, clay, aluminum oxide, iron, shale, and silica (along with lighter components separated from crude oil during its distillation) are combined with an energy source and heated up to 2,642°F (1,450°C) to make clinkers, which serve as the binder in cement products. Clinkers consist of calcium oxide (65%), silicon oxide or silica (20%), aluminum oxide (10%), and iron oxide (5%). Gypsum (calcium sulfate) and possibly additional cementitious compounds (such as blast furnace slag, coal fly ash, etc.), or inert materials like limestone are added to the clinkers. All constituents are then ground into a fine homogenous powder we call cement. The EUCIA paper calls glass fiber thermoset regrind an “ideal raw material for cement manufacturing. The mineral composition of the regrind is consistent with the optimum ratio between calcium oxide, silica, and aluminum oxide. Additionally, the organic fraction (i.e., resin) supplies fuel for the reaction heat, resulting in a significant reduction of CO2 emission.”

Based on discussions with Geocycle, RIMTA suggests that fiberglass waste could be introduced at several different stages of cement production, including the pretreatment of limestone in a kiln’s calcination tower. Fiberglass waste would be used primarily as a resource for heating and activating limestone as it moves through the tower. The constituent elements found in the ash of fiberglass waste (silica, alumina, etc.) would follow the limestone into the collective kiln feed and be encapsulated in the final product.

A document furnished by RIMTA to explain cement kiln function says Geocycle expressed interest in exploring pneumatic injection of fiberglass and other size-reduced waste directly into the arc of the kiln flame to provide a direct source of energy and thermal retention. The remaining constituent elements trapped inside the ash would become incorporated into the clinkers. One kiln in Northampton, Pennsylvania, is equipped for that procedure and expressed interest in fiberglass waste.

RIMTA broke down the cost structure of Phase One by order of magnitude: 59.1% ($500/ton) for shredding the vessels, which on average were 21‘ in length and yielded 1.4 t of material; 13% ($1.91/mile) for kiln delivery of the shredded material; 12.1% ($3.75/mile) for in-state transportation of boats from yards to the collection site; 8.4% ($65/ton) of kiln acceptance fees; and 7.4% ($20/hour) for prep/dismantling of boats. “In consideration of the average Phase One candidate [boat] (21.0 ft/6.4m, 1.4 t/3,100 lbs), current calculations indicate a total [disposal] cost of $1,136 per boat,” the report stated. “Excluding costs incurred by the participating marine industry businesses (preparations/dismantling and in-state transport), a general RIFVR acceptance fee can be deduced. That acceptance fee basis is $924 per boat, or approximately $44 per foot.” RIMTA indicated these numbers are merely a snapshot derived from the pilot and are subject to change as the program evolves.

One possibility to scale coprocessing could be a cross-platform approach combining similar waste streams, like those of old fiberglass boats and fiberglass wind-turbine-rotor blades that will be retired in large numbers around the world. WindEurope estimates around 14,000 blades could be de-commissioned by 2023, comprising between 40,000 and 60,000 tons of fiberglass. “If we can get the volume up as they’ve done in Europe with [decommissioned] wind turbine [blades], we’re hoping that we can see both sides of that process,” Ridley added.

Geocycle GmbH, an affiliate of Holcim (Germany) AG, which focuses on coprocessing of decommissioned wind blades with an annual processing capacity of 40,000 metric tons, stated that they select “previously audited GRP material (i.e., certain rotor wings of wind turbines), which does not include boat hulls.”

Blending ground boat hulls with other end-of-life fiberglass products to create a reliable and acceptable material supply for cement kiln use requires significant effort. “We’ve realized important things, not only for the short-term viability of recycling composites but for the long-term viability of a program like this,” Ridley said. “Presenting a consistent mixture of material to the end user builds a level of reliability that ultimately can influence the economics in a positive way,” he explained. “Producing a high volume of material and demonstrating that the makeup of that material never changes make the recycling job much easier. Looking at 40 years of boat construction and establishing a core group of materials that are compatible with recycling processes and are more predictable at their end of life would certainly help everyone.”

PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY

Scaling a coprocessing scheme for old fiberglass boats to a regional or national level will require a herculean effort on many fronts: collection, dismantling, crushing, grinding, and processing. But with buy-in from key stakeholders, the right incentives, and an educational push to change attitudes and behaviors, it is not out of reach, as we’ll discover in Part 2 of this series. Manufacturers, of course, are not oblivious to the benefits of sustainability and are quick to point to initiatives they have implemented or are in the process of introducing. Improving efficiencies, reducing waste and water consumption, incorporating recycled materials, switching to renewable energy, education and community support are typical talking points that echo Confessions of a Radical Industrialist, the 2009 book by Ray Anderson, the late CEO of carpet manufacturer Interface, which embraced sustainability to boost profitability.

In his 2020 IBEX presentation, Kevin Grodzki, boat-manufacturing giant Brunswick’s now-retired vice president of communications and public affairs, listed similar sustainability initiatives and also mentioned end-of-life boats and producer responsibility. Grodzki: “Customers are going to hold us accountable…. There will be a right time and a right place for the implementation of new designs and technologies and new formulations, but in the meantime we have an aging base of material. I believe that it’s going to be incumbent upon the industry to step in and make a difference.”

Brunswick, a sponsor of the RIMTA project, did not provide details or a sketch of what such a program could look like for a multinational company responsible to shareholders who might like to see solutions that consider the end of a product at the time of its manufacture. Some questions that come to mind: How much of an old boat or motor could find use in a new one? How do you design, engineer, and build mass-produced boats with renewable composite materials and resins, like some builders are exploring? (See also “The Quest for Cleaner Composites,” PBB No. 188.) Or how can smaller builders participate and benefit?

“The evolution will be driven more by innovation and technology, to some degree by regulation,” Grodzki said. “I believe it is incumbent upon every healthy industry to take control of its own destiny. In my judgment I would like to see less of it driven by regulation and more…by initiative, because it is the right thing to do.”

One initiative that impressed political leaders was the RIFVR pilot. In late August 2020, a joint press release by Rhode Island’s Congressional delegation, led by U.S. Senators Jack Reed and Sheldon Whitehouse, announced a $105,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program Foundation “to expand Rhode Island’s innovative fiberglass boat recycling program across New England and to the State of Washington.”

REALITY CHECK

Before old boats can disappear into the landfill or the cement kiln, they must be salvaged, detoxed, and dismantled. It’s the first, most important, and costliest step in disposal. “Abandoned fiberglass boats are releasing toxins and microplastics across the world,” wrote Corina Ciocan, senior lecturer in marine biology at the University of Brighton, in Marine Technology News. “Some say that dumped fiberglass boats will make suitable artificial reefs. However, very little research has been done on at-sea disposal and the worry is that eventually these boats will degrade and move with the currents and harm the coral reefs, ultimately breaking up into microplastics.” Those microparticles harm mangrove, seagrass, coral habitats, and marine life and eventually get into the food chain, exposing humans to chemicals that have been associated with ADHD, breast cancer, obesity, and male fertility issues. Ciocan also points out high concentrations of copper, zinc, and lead found in sediment samples and small marine organisms exposed to peeling paints of abandoned boats nearby. Other health hazards attributed to abandoned boats can come from rubber, plastic, wood, metal, textiles, and oil on board. Especially dangerous contaminants include asbestos insulation, classified neurotoxins from corrosion-inhibiting lead paints and mercury-based compounds, and tributyltin (TBT), a now widely banned antifouling agent.

Seeking to understand the status quo and the challenges on the front lines, I checked in with Troy Wood, who manages the Derelict Vessel Removal Program (DVRP) at the Aquatic Resources Division of the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR). “We wish we could remove all derelict and abandoned vessels from the waters of the state, but we are limited by the resources appropriated to the program through the legislature,” Wood explained. “The DVRP is considered the last resort when dealing with a vessel [even though] its owner is ultimately responsible.”

The 2002 Washington State Legislature passed the Derelict Vessel Act, which provides certain local and state agencies with the authority and funding for the removal and disposal of derelict and abandoned vessels from state waters. The DVRP has a two-year budget of $2.5 million funded by recreational vessel registration and commercial vessel fees and revenue from state-owned aquatic leases.

One challenge is coordinating the capabilities and authorities of the different federal agencies that may respond to reports of derelict vessels. Prior to 2002, DNR had to rely on the vessel owners’ cooperation or face lengthy legal procedures, including trespass and nuisance abatement actions, and federal actions to address derelict vessels. The U.S. Coast Guard and the Army Corps of Engineers have federal authority to deal with derelict and abandoned vessels, but their responsibilities differ. The USCG handles substantial pollution threats or threats to federal navigation channels. It removes pollutants and offending vessels that obstruct channels, if necessary. The Coast Guard does not have authority to remove and dispose of a vessel once the immediate threat has been addressed. The Corps removes floating or sunken debris but only if it’s a hazard to navigation in a federally maintained navigation channel.

The DVRP removed 924 derelict or abandoned vessels statewide dating back to 2003 and has a current inventory of approximately 235 listed as vessels of concern. “We are averaging around 100 [boats] and are currently at 60 removed for this biennium,” Wood said. “With limited resources we have to prioritize the vessels [posing a] high risk to human safety or the environment. It is becoming more expensive to remove and dispose of vessels every year. Contractor and landfill costs are on the rise, as well as the sizes of vessels needing to be removed.”

The average salvage cost for a recreational vessel, Wood said, is about $10,000 to $12,000, while derelict commercial vessels can cost between $30,000 and $400,000, depending on size, location, and circumstances. It’s an uphill battle with only three staff, none of whom is trained on the heavy equipment required for most dismantling or demolition. Time and capacity constraints require the DVRP to hire contractors, Wood added.

If hazardous materials on a boat exceed landfill limits, Wood and his staff remove the contaminants or find a landfill willing to accept the material. Hazardous material removal is very costly and accounts for much of the cost of removing commercial vessels. Wood said, “The DVRP looked into other sources of funding, but we have not been able to find a source that garnered general support.”

THE VOLUNTARY APPROACH

I found some good news in Washington State in the form of the DNR’s voluntary Vessel Turn-in Program (VTiP), which started in 2014 and dismantles boats less than 45‘ “that do not yet satisfy the definition of derelict or abandoned, but are likely to become derelict or abandoned in the near future,” the DNR website explains. In 2020 the Washington State Legislature lifted the program’s rather small spending cap of $200,000, so it can remove more boats before they become abandoned or derelict, with priority based on threats to human safety or the environment. To stretch the budget until June 2021, the VTiP, which also receives funding and promotional support from WA Sea Grant, has to batch the disposal projects based on priority level and location. The $4,000 average removal cost per boat tallied for the VTiP is much lower than for the DVRP.

Looking past salvage and dismantling, bringing the cement kiln coprocessing program to the State of Washington has been slowed by the COVID pandemic, WA Sea Grant’s Barnett said. “$100,000 were set aside for [a] research budget, but the Governor vetoed it last summer.” And there are other hurdles: A suitable chipper has to be found, and safety issues must be addressed after a processing test sent one employee to the ER with severe particulate irritation. “A market-based solution will emerge when the time is right,” Barnett concluded. “The infrastructure is available…. It’s baby steps right now. But they are going in the right direction.”

Until that market-based solution emerges, prompted by financial expedience or regulatory prodding, it appears that the most likely course for dead old boats is to follow our recyclable plastic salad boxes into the landfill, where they’ll get bulldozed with the rest of our garbage.

In PBB No. 190, Part 2 of this series will cover ideas, opinions, and solutions in other countries grappling with the disposal of end-of-life fiberglass boats.

TIMBER

- This is a wooden boat being dismantled. The engine and other parts might

go to another boat. While the wood will be typically crunched up for

chipboard, since planking is very hard to salvage. The good news being that

woods rots away naturally.

THE GUARDIAN - 6 AUGUST 2020 - NAUTICAL NOT NICE: HOW FIBREGLASS BOATS HAVE BECOME A GLOBAL POLLUTION PROBLEM

Fibreglass fuelled a boating boom. But now dumped and ageing craft are breaking up, releasing toxins and microplastics across the world.

Where do old boats go to die? The cynical answer is they are put on eBay for a few pennies in the hope they become some other ignorant dreamer’s problem.

As a marine biologist, I am increasingly aware that the casual disposal of boats made out of fibreglass is harming our coastal marine life. The problem of end-of-life boat management and disposal has gone global, and some island nations are even worried about their already overstretched landfill.

The strength and durability of fibreglass transformed the boating industry and made it possible to mass produce small leisure craft (larger vessels like cruise ships or fishing trawlers need a more solid material like aluminium or

steel). However, boats that were built in the fibreglass boom of the 1960s and 1970s are now dying.

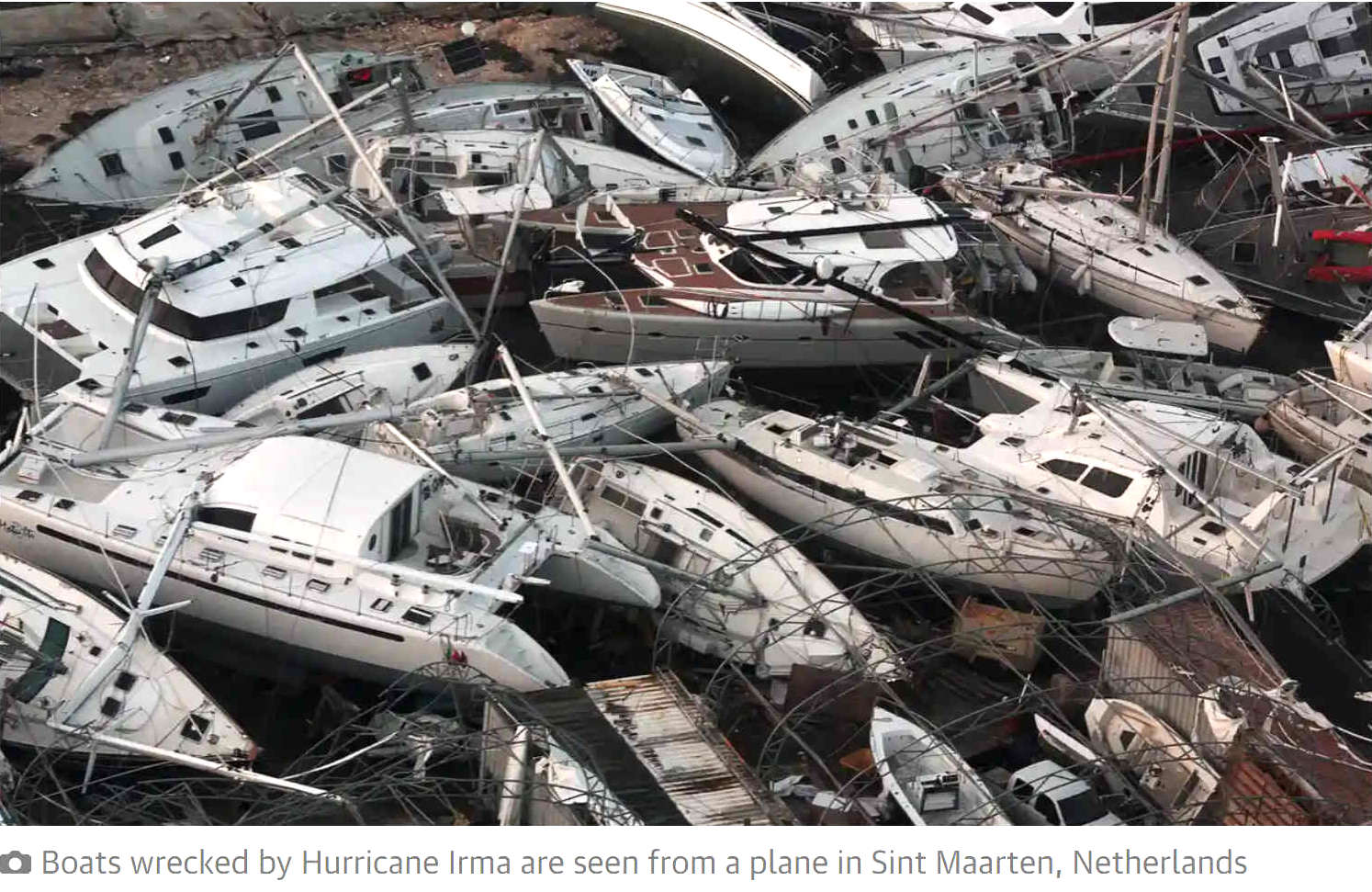

We need a drain hole for old boats. We can sink them, bury them, cut them to pieces, grind them or even fill them with compost and make a great welcoming sign, right in the middle of roundabouts in seaside towns.

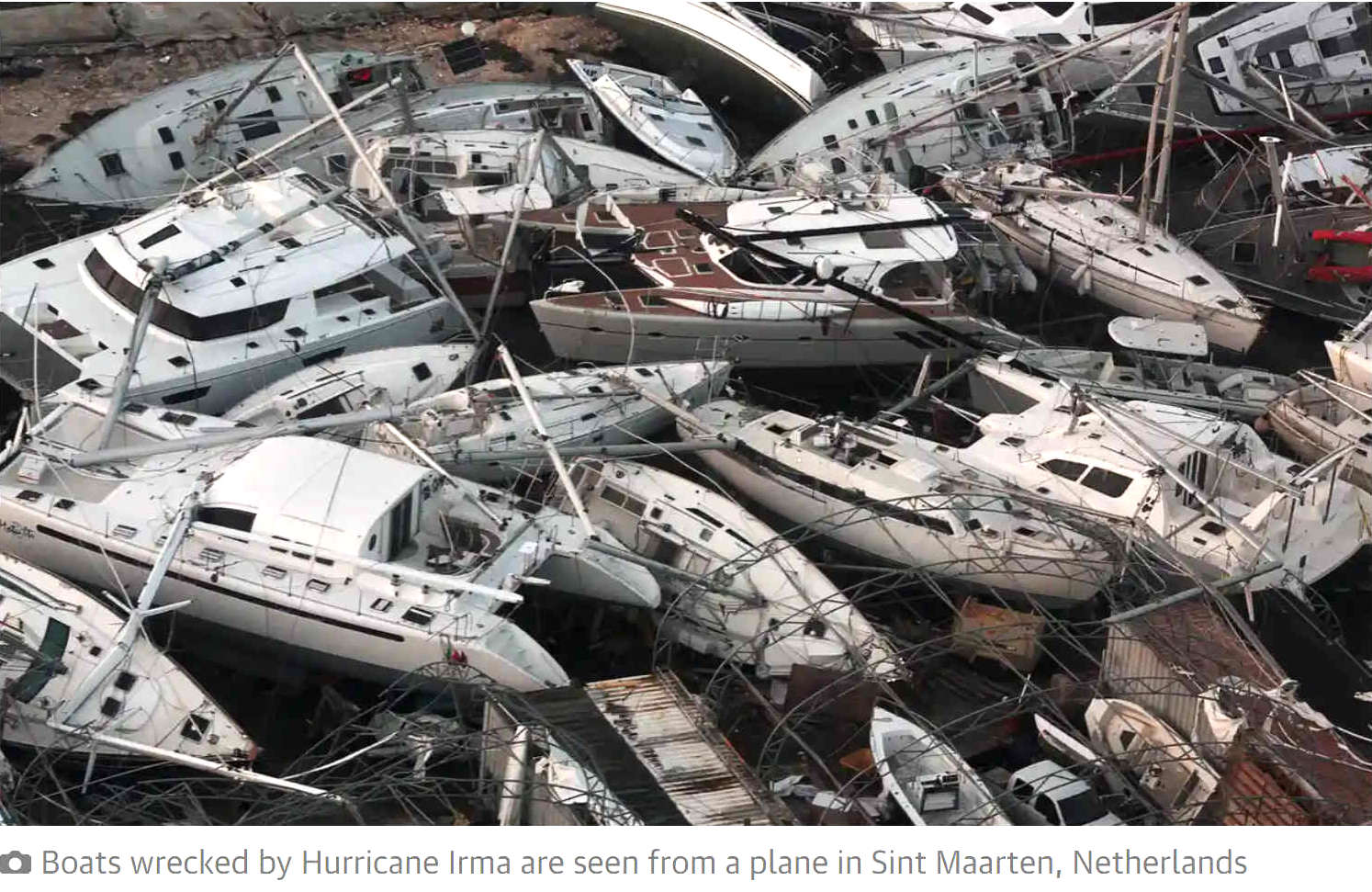

But there are too many of them and we’re running out of space. To add to the problem, the hurricane season wreaks havoc through the marinas in some parts of the world, with 63,000 boats damaged or destroyed after Irma and Harvey in the Caribbean in 2017 alone.

Most boats currently head to landfill. However, many are also disposed of at sea, usually by simply drilling a hole in the hull and leaving it to sink someplace offshore.

Some say that dumped fibreglass boats will make suitable artificial reefs. However, very little research has been done on at-sea disposal and the worry is that eventually these boats will degrade and move with the currents and harm the coral reefs, ultimately breaking up into microplastics. Recently, scientists have investigated the damage to mangrove, seagrass and coral habitats and although the effects have only been recorded on a relatively localised basis for now, the cumulative effect of abandoned boats may increase exponentially in the coming years.

To take one example, researchers from Plymouth University found high concentrations of copper, zinc and lead in sediment samples and inside the guts of ragworms in two estuaries in eastern England (Orwell and Blackwater). These contaminants greatly exceeded the environmental quality guidelines, and came from peeling paints from boats abandoned nearby.

Since no registration is needed for leisure vessels, the boats are often dumped once the cost of disposal exceeds the resale value, becoming the liability of the unlucky landowner. Human health hazards arise from chemicals or materials used in the boat: rubber, plastic, wood, metal, textiles and of course oil. Moreover, asbestos was employed extensively as an insulator on exhausts and leaded paints were commonly used as a corrosion inhibitor, alongside mercury-based compounds and tributyltin (TBT) as antifouling agents. Although we lack evidence on the human impact of TBT, lead and mercury are recognised as neurotoxins.

And then there are the repairs – grinding away at fibreglass boats, often in the open, creates clouds of airborne dust. Workers have not always worn masks and some succumbed to asbestosis-like diseases. Inevitably, some of the dust would find its way back into the water.

The fibreglass is filtered by marine shellfish (in my own research I found up to 7,000 small shards in

oysters in Chichester Harbour in southern England) or cling on the shells of tiny water fleas and sink them to the seafloor. The particulate material accumulated in the stomach of shellfish can block their intestinal tracts and eventually lead to death through malnutrition and starvation.

The microparticles stuck on water fleas may have repercussions for swimming and locomotion in general, therefore limiting the ability of the organisms to detect prey, feed, reproduce, and evade predators. There is huge potential for these tiny specks of old boats to accumulate in bigger animals as they are transferred up the food chain.

Those microparticles are the resins holding the fibreglass together and contain phthalates, a massive group of chemicals associated with severe human health impacts from ADHD to

breast

cancer, obesity and male fertility issues.

Abandoned boats are now a common sight on many estuaries and beaches, leaking heavy metals, microglass and phthalates: we really must start paying attention to the hazard they pose to human health and the threats to local ecology.

By Corina Ciocan - a senior lecturer in marine biology at the University of Brighton.

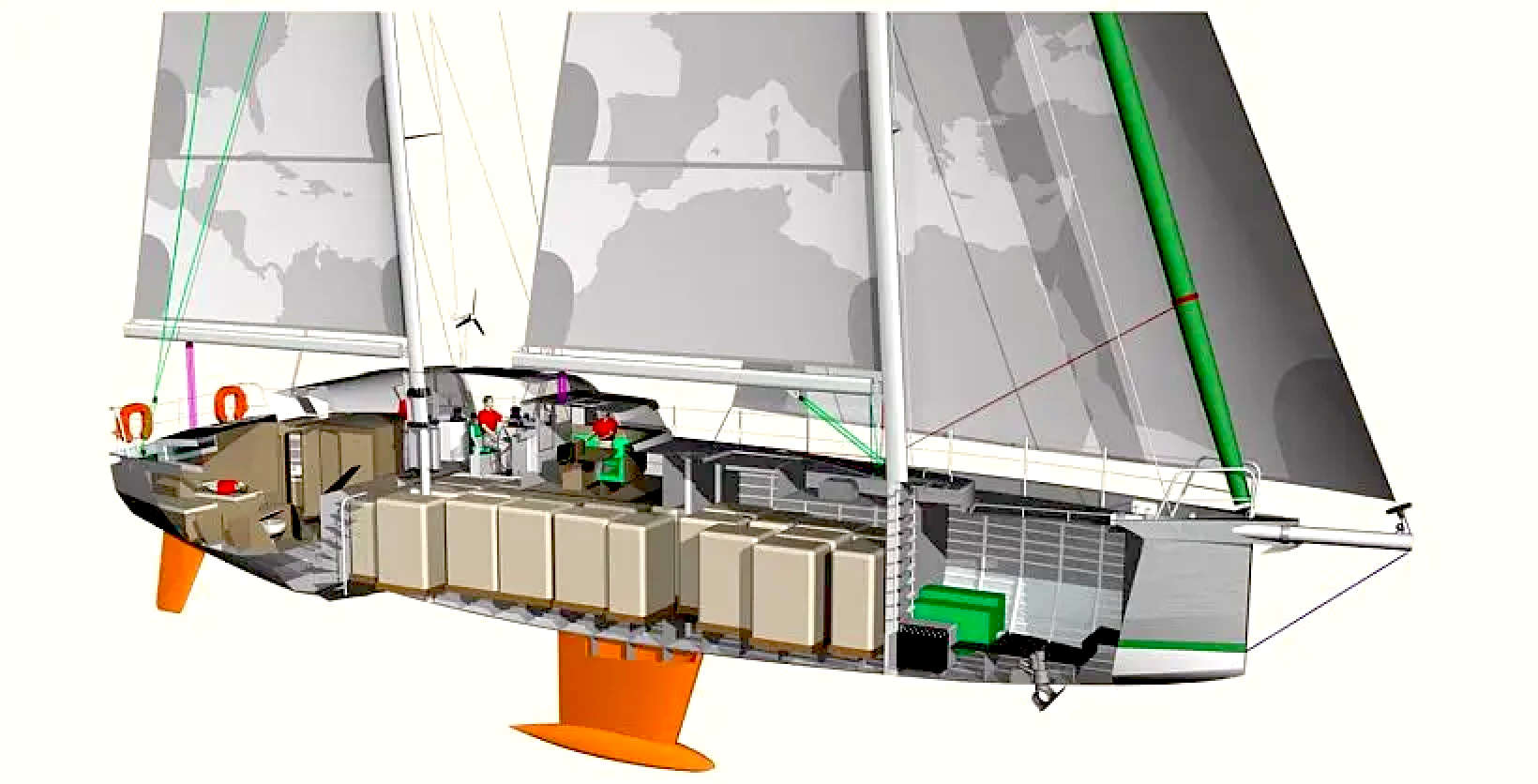

WAY

TO GO - ZERO PLASTIC SHIP The

Elizabeth Swann is a plastic free

ship, designed to be built in 5083 marine

grade alloy, such as to be 100% percent recyclable, with an exceptionally

long service life. No Glass Reinforced Plastic (GRP)

is to be used in the hull construction. In

addition, single use plastic for disposable items such as toothbrushes,

and food packaging will

be replaced with natural. PRACTICAL BOAT OWNER JULY 28 2020 - PLASTIC BOATS - HOW SHOULD WE DISPOSE OF OLD BOATS WHEN THEY REACH THE END OF THEIR LIVES?

The disposal of plastic boats is a growing problem. PBO is passionate about restoring old boats, but what happens when they’re beyond repair? Nic Compton looks at some of the solutions.

Steve Franklin is on a mission. He’s made it his business to deal with the increasing numbers of boats in the UK reaching the end of their useful lives, too many of which end up abandoned in marinas or cluttering up creeks around the country. It’s a growing problem which the UK’s boating industry – unlike most other European countries – seems to be reluctant to deal with. And it’s driving this self-appointed Undertaker of the Boating World a little bit nuts.

“It’s about blasted time people started listening to us,” he says, when I speak to him on the phone to arrange an interview. “We need people everywhere to look for more effective solutions, because the problem isn’t getting any better.”

And certainly the figures make uncomfortable reading. According to a recent study, there are 6 million boats in the EU, about 95% of which are made of GRP. Every year, around 1-2% (ie 60,000-120,000) of these boats reach the end of their useful life. Of these, only 2,000 are recycled, while another 6,000-9,000 are abandoned in a variety of unsightly ways. The rest are presumably being kept by reluctant owners at their own expense.

“No-one wants to accept liability for end of life,” says Steve. “Boat insurance companies say they don’t break boats up; they give them back to the owners who have to deal with it. Marinas won’t pay to have abandoned boats removed; they just put them on ebay and sell them for £1 to get rid of them. Anyone can buy a boat for £1, strip it of all the good bits and then dump it somewhere. Who’s then liable? Not the marina, because they sold the boat for £1. The owner can’t be traced, because we don’t have an owner registration scheme. So it’s the local council that has to deal with it, and local taxpayers have to pay the bill. It’s so unethical.”

The problem, as usual, is money; who pays for these old boats to be disposed of? Under the current UK model, whoever happens to own the boat when it reaches the end of its life has to pick up the tab. That seems fair enough, but in fact that person is probably the least likely to be able to afford to pay for this service.

Because boat breaking is not cheap. EU research suggests it costs around €800 to dispose of a 23-footer, rising to €1,500 for a 33-39ft boat and up to €15,000 for boats over 50ft long. Boatbreakers themselves put the price at about £100 per foot – ie £3,000 for a 30ft yacht (though contact them directly for a detailed quote, as it may be less depending on location, etc).

While I was researching this article, I heard from a boatyard in Cornwall which had to pay nearly £40,000 to dispose of two wooden MFVs that had been abandoned on its premises.

So who should pay for this? What about the original owner who commissioned the boat in the first place? Or the builders who profited from selling it? Or all the other owners down the line who enjoyed sailing the boat and were once proud to call it their own? Inevitably, as the boat gets older and its value diminishes, it ends up in the hands of the less wealthy and in cheaper moorings – which is why so many backwater yards end up with so many old wrecks. And by definition these are the very owners and boatyards that can least afford to pay for the boat’s disposal.

The result is an increasing number of boat graveyards where boats are dumped without any means of tracing the owner. The local council, or worse, the Harbour Board (which has a fraction of the budget) is then faced with the difficult choice of whether to dispose of the boats at their own expense, thereby providing a de facto free boat recycling service, or leave them to pile up and become more of an eyesore and possible health and environmental risk.

It’s a natural cycle which has been going on for years, but the problem is set to reach crisis point as the boatbuilding boom of the 1960s and 70s catches up with us and thousands of (mostly GRP) boats reach the end of their useful lives.

Combine that with a declining interest in sailing among younger people and a glut of second-hand boats on the market leading to a decline in the value of old boats, and we really are heading for a perfect storm. All this at time when concern for the environment is reaching fever pitch, and it really won’t do to simply scuttle boats out at sea and not worry about the consequences.

For it turns out that, far from creating a natural habitat for sea life, scuttled boats tend to move around on the seabed, destroying

coral in tropical areas and damaging precious sea grass in northern climes. And that’s not to mention the unknown repercussions of the chemicals and micro-plastics which are released into the sea as the boat degrades.

“It’s worse for boats than it is for cars,” says Boatbreakers’ communications manager Luke Edney. “With cars, the value drops and drops, and then levels out, because you can always get £50 for scrap. Whereas with boats, the value drops and drops and then goes below zero, because it’s going to cost you £20,000 to get it scrapped if it’s a big one. We get people calling who haven’t been able to sell their boats and are worried about paying their marina fees. They would rather pay for the boat to be scrapped than have to pay more bills. It’s a relief for them not to have to worry about it any more.”

There are, however, solutions to the problem both of what to do with the old boats and how to finance their disposal – though most of that progress is being made outside the UK.

The EU has commissioned two major projects into boat recycling: Boatcycle (2010-12) which produced guidelines for building boats in a more sustainable way in the first place as well as instructions for dismantling and recycling end-of-life boats, and Boat DIGEST (2013-15), which provides training and accreditation for boat dismantling.

Neither, however, addressed the thorny issue of who should pay the cost of scrapping.

One possible solution is a national boat recycling scheme funded by a tax at the point of sale and/or as a levy on boat insurance. The money would be collected by a regulatory authority and used to dispose of old boats.

“The solution is for people to stand up and accept responsibility for their position,” says Steve. “We need a European-wide remit to capture that money from anybody who owns a boat, from a dinghy right up to a Sunseeker. It all comes from the same kind of material, and you’ve still got to get rid of it. There should be a premium either on insurance or on new sales – like they do with cars – so that when a boat reaches the end of its life the owner can just ring Boatbreakers, or whoever, and ask us to collect it for disposal, no matter how much they paid for it or how old the boat is.”

SHOULD THERE BE A SALES TAX ON BUYING A BOAT ?

The idea of a sales tax is supported by Phil Horton, the RYA’s environment and sustainability manager, who sees it as part of a broader picture.

“We need to consider the issue of extended producer responsibility,” he says. “Boat manufacturers need to think about the long-term impact of what they are doing and contribute to the boats’ eventual disposal. It’s like batteries: you can take any make of battery to a recycling centre because manufacturers are required by law to join the Battery Compliance Scheme and pay for old batteries to be recycled.”

Elsewhere in the world, governments are taking a more proactive approach and dealing with the growing problem of abandoned boats. In Canada, the government has paid to have derelict boats removed from its coasts. In 2018, the Swedish government provided r300,000 in subsidies to scrap 500 boats under 3 tonnes free of charge, providing the owners paid for transportation costs.

But France seems to have found the best solution. Thanks to new rules introduced in 2019, owners are required to pay an ‘eco tax’ when they register their boats – which is obligatory – and the funds generated are used to scrap old ones. As in Sweden, all the owners have to do is have the boat transported to an approved recycling centre.

[Boats should be tagged electronically, with registration of the owners and

legal transfers of title. No registration fees, to encourage responsible

behaviour, but huge fines for boats that are missing and not reported lost

at sea.]

The problem has even reached Tahiti, where boats are regularly dumped and their owners vanish without trace. On such a small island there are limited landfill options, so dealing with these derelict hulls is a growing problem. So much so that marine ecologist Simon Bray was commissioned to write a report for the

United

Nations. His conclusion echoes the views of Boatbreakers and the RYA.

“Legislation will be the driver of change,” he wrote. “The most feasible routes towards funding future recycling appear to be levy systems on new boat sales and on ownership registration leading to centralised funds to back up vessel recycling programmes.”

So far, the British government has taken a lackadaisical attitude to the problem, but the growing interest in environmental issues and in particular about plastic pollution is likely to change all that.

“If you try to talk to government about old boats, they say it’s a boating problem and it’s up to the boating sector to sort it out,” says Luke. “But if you say it’s non-recyclable plastic boats being dumped around the country, alarm bells start ringing. That opens up opportunities for conversations with government.”

It’s a subject close to Steve’s heart and something this former navy man turned boat entrepreneur has been banging on about for over a decade.

Having trained as a boat surveyor in the mid 2000s, Steve found himself writing off more and more old boats and wondered what happened to them next. A bit of research showed that no-one in the UK was offering a boat breaking service, and so Boatbreakers was born. What started as a business opportunity gradually developed more of an environmental purpose.

“At that time, we threw everything away,” Steve says. “Engines went to the car breakers, masts to the metal scrap yard. We’ve evolved since then, and we’ve developed processes to deal with all parts of the boat safely and to recycle as much as possible. Our policy is to do it right, even though it costs us more to do it right – and anyway DEFRA won’t let us do it any other way!

“To start with, we set aside various hazardous materials – fuel, oils, gasses and anything else that might harm the environment – which we take out and put to one side. Then we take the engine out and remove the oil, we take the fuel tank out and empty the fuel – all the oil and fuel goes for recycling. If the mast is reusable, we’ll set it aside, stack it and offer it for sale; if it’s old there’s no point, so we’ll squash it down into a cube and that goes to recycling and gets melted down. Whatever we can repurpose we now keep – we don’t just bin it.”

Steve estimates the fittings and other parts make up about 30% of the boat, of which they repurpose more than 90% (amounting to 28% of the whole boat). In fact, selling second-hand boat parts salvaged from old boats is an essential part of the business, and Boatbreakers have a warehouse full of bits they sell on the internet. Steve reckons they’ve accumulated some 100,000 boat bits (“Though it might be a million, who can tell?”) ranging from portholes to foul weather gear, bathing ladders,

engine parts, winches, windlasses, saloon tables and even pots of paint.

He sells whole engines, though out of the 200 boats the company has broken up in the last year, Steve reckons they only pulled out ten really good engines for resale. “Owners know engines have value, so they often take them out and sell them themselves before we get there.”

Once the hull is stripped of all its fittings, the bare hull is then crushed and the remains dealt with accordingly. Of the yard’s current intake of about 200 boats per year, Steve reckons 70% are GRP and 30% are

wood – they receive hardly any metal boats, partly because there are less of them in the first place but also because owners can sell them for scrap. Some car breakers accept metal boats and will pay the going rate for the metal they contain.

If the boat is GRP, the story ends there. There is currently no process in the UK for recycling glassfibre, so the chopped up hulls go straight to landfill – which Boatbreakers have to pay for. Part of the problem is that a boat’s hull is a composite, made up of gelcoat, followed by glassfibre, followed by a foam or balsa core, followed by more glassfibre or other lining, with extra layers of glassfibre, wood and/or metal reinforcement in strategic locations around the hull. Separating the various elements is an expensive process and the end result is something which at the moment has little or no commercial value – unlike

carbon fibre, where the raw materials are expensive enough to warrant recycling.

RECYCLING FIBREGLASS

There are options for re-using fibreglass which are being trialled in other countries. In the USA, a company called Eco-wolf has been grinding down fibreglass since the 1970s and using it to make bathtubs and railways sleepers – as well as turning it into filler for boat repairs. A company in Norway is grinding the stuff down and turning it into flowerpots and benches.

Other options include chopping it up and mixing it with asphalt to produce a hard-wearing road surfacing material, or burning it to produce energy – at extremely high temperatures, burning fibreglass is surprisingly clean, though it produces a lot of waste ash which then has to be disposed of, usually through landfill.

The problem is particularly acute in Germany where, due mainly to the high number of wind turbine blades reaching their end of life, fibreglass has been banned from going to landfill. Instead, old fibreglass is ground down and mixed in a cement kiln to produce concrete – a model replicated in Rhode Island, USA, and elsewhere. Indeed, this is probably one of the most successful uses for the material.

And there are some unexpected artistic uses for old boats. “We had a call from a design student in London who wanted some fibreglass to make recycled tiles from,” says Steve. “So we found some thin bits from an old dinghy for him, and it ended up being exhibited at the Milan design show!”

A few lucky boats that are in good condition are restored and sold on – with the previous owner’s consent. But, worryingly, for owners of older fibreglass boats, Steve has noticed that hulls that are more than about 25 years old are much less resilient than newer boats.

“When we break up a boat that’s more than 25 years old, the hull shatters because the fibreglass is really brittle. A newer boat is much more pliable and more resilient to the crushing machine.”

The situation is a little better for wooden boats – though lovers of venerable old classics which have gone past their prime should skip the next couple of paragraphs.

“Wooden boats shatter up quite nicely into shards of wood,” says Steve. “Teak mahogany, or whatever. It all goes in the wood bin and probably ends up as chipboard. People think we take off each plank individually, but we would just end up with piles of wood of all kinds of strange shapes that we could never sell.

“Anyway, most of it is as rotten as a peach and can’t be repurposed: remember it’s coming here because it’s been damaged or written off. Some wooden boats are literally falling apart as they come off the lorry. Once we take them apart, the keels are usually black, wet and rotten, and the cost of repair is more than the boat’s worth.

“It’s a shocking idea this, that a lovely old boat built in the 1930s, at the very peak of the wooden boatbuilding era, using the best quality timber – probably better than anything available today – should be crushed and turned into chipboard. But what are the alternatives? There are only so many pubs that can turn a clinker hull into a characterful bar or quirky seat. Turn them upside down and turn them into sheds and cabins to let on Airbnb? Again, it’s a limited market.

“It’s a shame to have to do it, but that’s the reality of it,” says Steve.

“The most uncomfortable part of the process for me is if the owner is there and he or she breaks down. It happens a lot, and I genuinely have empathy for people because it’s their personal history we’re taking away. And it’s not their fault the boat has got to that point, because fibreglass doesn’t last forever.

“There was one small yacht this guy had owned since it was new. He’d taken his kids out on it, but now the kids were grown up and no-one wanted it anymore. When I got there, the wife was there, as well as the mum and dad, and the son and daughter; they were all in a row crying. I don’t care so much about the boats, but I do care about the owners. Because it’s a difficult job; we are the undertakers, and we have to have some empathy towards them.”

One of the main obstacles faced by boat breakers in the UK is the issue of transport – the cost of getting the boats to the breaker’s yard is usually the most expensive part of the process. Steve hopes to address this problem by franchising the Boatbreakers brand and creating a network of yards around the UK, so that boats can be disposed of locally rather than transported to his yard in Portsmouth. That in turn would reduce the cost of the service and hopefully encourage people to dispose of their boats responsibly rather than dumping them.

The only take up so far has been a possible outpost in Poland, but Steve is hopeful there will soon be branches of Boatbreakers springing up all around the country.

The other big issue facing Boatbreakers – and boat breakers more generally – is finding a commercial use for old fibreglass, whether it comes from old boats, wind generators or old caravans. Once the material has some commercial value, then the cost of breaking boats will become more affordable and, who knows, old hulls might one day acquire some value as scrap. In which case owners will be queuing up to take their old boats to the knacker’s yard.

Last but not least, Steve believes there should be greater accountability for owners. “You can’t abandon a car because there’s a number on it; that number is linked to a logbook, and that logbook is linked to the owner via the DVLA. But boats in the UK can’t be traced to individual owners.

“The Small Ships Register isn’t effective because it’s a voluntary scheme which isn’t automatically updated. We could scoop up boats all day long if we could trace their owners. We need a legal scheme to register owners and boats so that they can be traced to determine who is responsible for the end of life.”

Owner registration, extended producer responsibility, a national boat recycling scheme – these are all possible solutions to this increasingly intractable problem. And it’s an issue which is only likely to get much, much worse. Unless something is done, we will continue to rely on the honesty of individual boat owners to do the right thing, and there will always be those who take advantages of the many loopholes in the current system.

It all makes perfect sense, and I’m absolutely persuaded by all the arguments in favour of boat recycling. However, the weather was foul when I visited Boatbreakers and I didn’t get to see the yard in action, so when I get home I decide to watch it online. Steve and Luke have not only featured in several episodes of Scrap Kings on Quest TV (dplay.co.uk) but have their own YouTube channel Boatbreakers Video.

Watching them at work was a mistake. I can barely look as a seemingly sound Hillyard 9-tonner is demolished in minutes by a digger, while Steve chats happily to the camera.

And suddenly it dawns on me: this really is an end of life scene and Steve really is the undertaker, and of course death is never pretty. The best we can hope for is that our ashes will fertilise a plant, or that a chopped hull will feed a furnace or pave some roads. It’s all part of the cycle of life.

Old boats RIP.

Hurricanes

and other extreme weather conditions quite often result in boats being

washed out to sea, or piled up as wrecks, just waiting to start the

degradation process, as they add to marine pollution.

BOATING INDUSTRY CANADA 2 MARCH 2021 - IS FIBERGLASS RECYCLABLE? PART 1

Today many things are made from fiberglass, from automotive parts to boats, and bathtubs to wind turbine blades. Fiberglass is lightweight and strong, it is resistant to impact and is waterproof. It does not rot and can be repaired relatively easily. But recycling fiberglass, can it be done?

While the short answer is yes, there is more to it than that. Shredding or grinding the

fiberglass destroys many of the glass fibers, reducing their size, strength, and therefore the usefulness for future applications. It’s not as simple as recycling other plastics because of the glass fiber content.

I learned to sail with my Dad and now I have a 1968 Colombia 22. The old guy who I got the boat from knew it needed either a lot of love or was destined to go to the landfill. It was eight long months of nights and weekends restoring and repairing the boat. Bringing the old fiberglass boat back to life and enjoying it on the fresh waters of Lake Michigan was priceless.

In my adventures of the beaches and waterways, I have been surprised at the number of

plastic

bottles, mylar balloons, and trash. With the pollution and plastic, I picked up, many times I returned to my car with a full bag of trash. Picking up trash and plastic when I find it is a good habit that I always have practiced. But it can feel like it doesn’t make much of a difference in the pollution problem.

Now I am living in Central America, where the garbage and recycling is not treated the same as in the United States or Canada. There are many places along the roads where trash is just dumped and not covered up. I have the opportunity to go the

Pacific Ocean in a short 40 minute drive, and see the plastic washing up on the beaches. It makes one aware of the need to deal properly with plastic waste. Like older boats.

The boating industry was and is a very big producer of fiberglass, changing the scene in the 1960s. Boats could be made much more quickly and cheaply, and the boats didn’t rot and need constant maintenance like the previous wood boats. This opened the market up to many people that otherwise would not have been able to afford a boat.

Jay

Weaver saved this Columbia 22 from a landfill site in 2019. GRP opened up

boating to the masses. Marinas are awash with everything from motor-sailers

to powerboats and giant yachts - mostly gleaming white glassfibre hulls.

They will all be retired one day, especially those powered by traditional

diesel engines. But it is up to the then owners to do the right thing.

Illegal dumping is not enforced. And landfill sites still accept fibreglass

boats.

But now many of those 50 and 60-year-old boats cost more to get rid of them than they are worth. It’s sad to see some of the classic boats come to the end of their useable lives. Many have been neglected and haven’t been properly maintained properly and the ingress of water in the wood sandwich decks and through leaky windows cause damage that costs more to fix than the boat is WORTH.

There is also the effect of hurricanes; the Boat Owners Association of The United States (BoatUS), estimates that more than 63,000 recreational boats were damaged or destroyed as a result of both

Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Irma. The combined dollar damage estimate is $655 million. The most common method for the end of life of one of these boats is to remove the good parts and send the fiberglass hull to the landfill.

The automobile industries in the United States and Europe have done research into recycling fiberglass car bodies and determining how to do it. Automotive recycling is a significant and growing component of automobile manufacturing and for the same reason faced by the

boat building industry, and that is too many cars on the road slowing sales of new cars.

The boat building industry has made only small and sporadic attempts to recycle its products, certainly nothing on the scale of the automobile industry. And boats have some particularly undesirable features that make them much more difficult to recycle than cars. But that is how we see it today, with innovation and making recycling more common, it’s likely that more opportunities will arise for the old boats.

The author, Jay Weaver, grew up sailing with his Dad in Michigan, and recently restored his 1968 Columbia 22 that he sailed on Muskegon Lake and Lake Michigan. Currently

(2021) living in El Salvador, he became much more aware of the environmental impact of plastic pollution in nature and the ocean.

The German company

Timbercoast, created by Cornelius Bockermann in 2014, is hauling rum, coffee, and cacao from the Caribbean, back to Europe. Much like the

sailing ships of the 1700s, it’s not an easy business, but he has a

mainstay of sailors who are assisted by volunteers who want to learn to sail and support sail cargo ships to reduce pollution.

He