|

PLASTICENE AGE

PLEASE USE OUR A-Z INDEX TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE

INDIAN EXPRESS MAY 2019 - Next, Plasticene

Humans have also left their mark on the Holocene, the era which began about 11,650 years ago, when the glaciers retreated. Ruined cities like Petra and Ur are stirring tourist attractions. Further back in time are the odds and ends of material culture — Acheulian hand-axes, Jomon pottery — and much further back are fossils like Lucy, and fossilised human footprints on the sands of time. Signs of the Anthropocene are less poetic — traces of pollution in tree rings, layers of soot in the substrata of industrial towns, massive deforestation and erosion, millions of acres of concrete, space junk in orbit.

However, there is time yet, until 2021. Time to define a subsidiary age of the Anthropocene, in recognition of a human stain that is far more pervasive than all these vile signs — plastic. Undegraded plastic is everywhere, from landfills to kitchens and the innards of cows. Rivers of plastic flow down to the sea, where it breaks down into microscopic particles that are now found in maritime life forms. Plastic is the most enduring sign of the human race. It is significant enough to be eponymous, identifying a subsidiary of the Anthropocene. It must be named Plasticene.

SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE JAN 2016

The last geologic epoch, the Holocene, is thought to encompass both the Bronze and Iron Ages. But we do not yet have a tool or material to define our current age. Scientists point to a few specifics changes that humans have wrought on the planet, including nuclear fallout and the rapid spread of materials like aluminum, concrete, and silicon as forensic proofs of humanity’s influence on Earth.

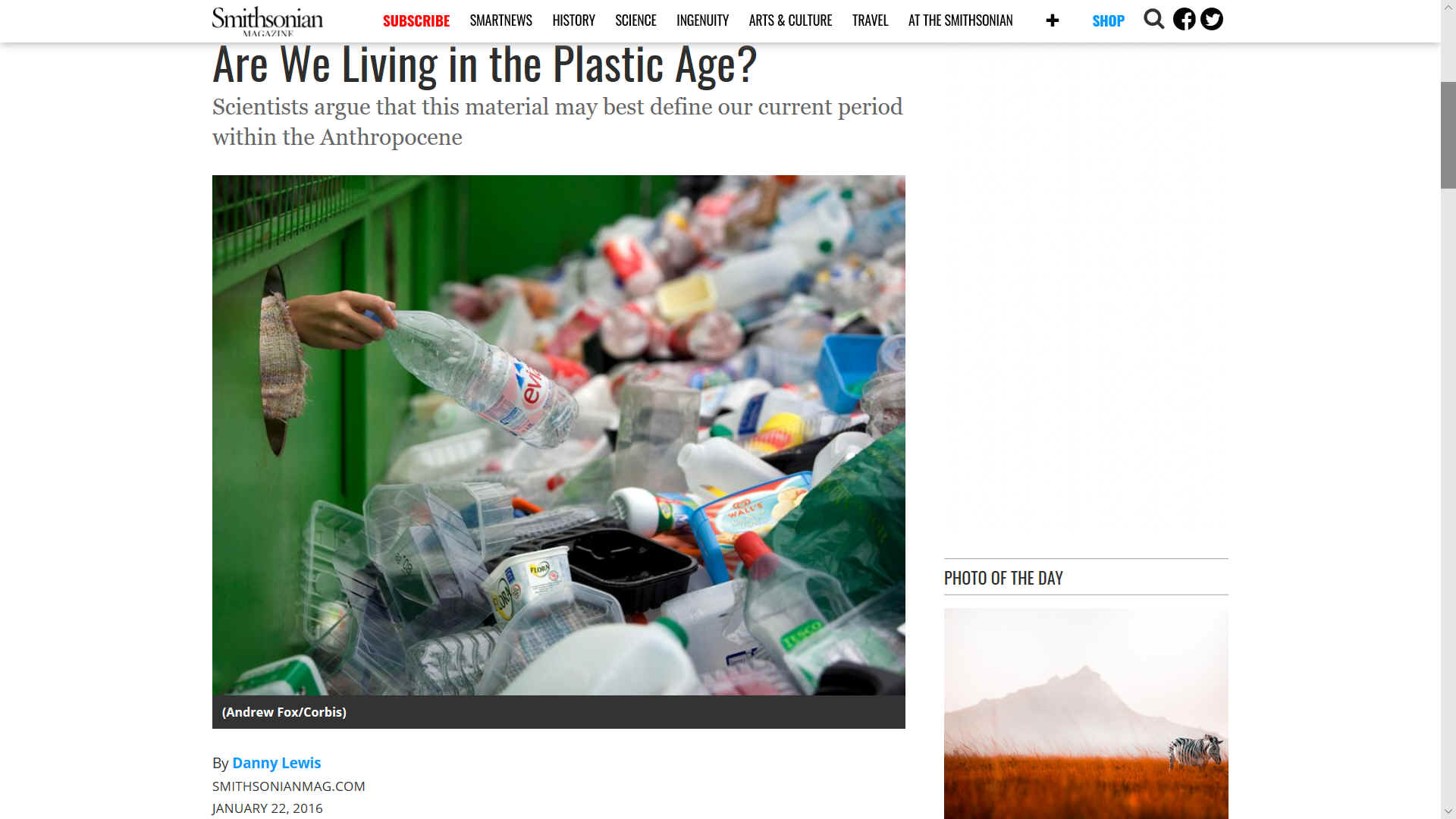

But according to archaeologist John Marston, plastic "has redefined our material culture and the artifacts we leave behind," and "will be found in stratified layers in our trash deposits," Giamo reports.

To add to the problem, most plastics don't easily degrade, and recycling isn't an adequate solution. Not all types of plastic are easily recyclable, and there are only a few recycling plants in the United States that can process all varieties of plastic.

This means that much of the materials thrown into recycling bins can crisscross the planet several times before they are processed to produce rugs, sweaters, or other bottles, Debra Winter writes for The Atlantic. Although millions of tons of plastic are recycled every year, millions more end up in landfills or the ocean. The problem has reached the point where it's possible that in just a few decades there might be more plastic in the world's oceans than fish.

"With a presumed life span of over 500 years, it’s safe to say that every plastic bottle you have used exists somewhere on this planet, in some form or another," Winter writes.

Even if human populations worldwide change their plastic-using ways, the damage may already be done. With plastics filling landfills and washing up on coastlines around the world, the Plastic Age might soon take its place next to the Bronze Age and the Iron Age in the history of human civilization. By Danny Lewis

FEBRUARY 2015 - The sixth planet, Welcome to the Plasticene

Along Florida’s coasts, brown pelicans diving for fish sometimes dive for the bait on a fisherman’s line. Cutting the bird loose only makes the problem worse, as the pelican gets its wings and feet tangled in the line, or gets snagged onto a tree.

NEW SCIENTIST JAN 2015 - Plastic Age: How it's reshaping rocks, oceans and life

Our addiction to plastics, combined with a reticence to recycle, means the stuff is already leaving its mark on our planet’s geology. Of the 300 million tonnes of plastics produced annually, about a third is chucked away soon after use. Much is buried in landfill where it will probably remain, but a huge amount ends up in the oceans. “All the plastics that have ever been made are already enough to wrap the whole world in plastic film,” palaeobiologist Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester, UK, recently told a conference in Berlin, Germany. It sounds enough to asphyxiate the planet.

What will become of this debris? Landfill will stay buried until future generations rediscover it, but it’s a different story for plastic that reaches the ocean. Some is washed up on beaches or eaten by wildlife. Most remains in the sea where it breaks down into small fragments. However, our knowledge of its ultimate fate is hazy. We don’t really know how much plastic pollution is choking the seas. Nor do we understand its potential impact on the health of sea creatures and those who eat them. Nor do we have any idea where the stuff will end up in the distant future – will plastic debris break down entirely or will it leave a permanent mark? By Christina Reed

LINKS & REFERENCE

https://anshikasawaram.wordpress.com/2015/02/02/the-sixth-planet-welcome-to-the-plasticene/ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/are-we-living-plastic-age-180957817/ https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22530060-200-plastic-age-how-its-reshaping-rocks-oceans-and-life/

ARE PLANET EARTH'S POLICIES WORKING? - If they were, we'd not have plastic poisoning the marine environment, or global warming. The problem is world leaders rely too much on fossil fuels and do not want to rock the boat until there is a solid backup plan, but the backup plan involves change. And that frightens them to stay put even though the water is already bubbling.

We cotton to that. Nobody likes change. But instead of overheating the planet and killing life undersea with toxic plastic, surely it would make sense to brave the new world and accelerate the adoption of renewables and a society that cleans up after itself. We need new sustainable infrastructures to save PLANET A and a gradual changeover plan that sits well with stakeholders. Not to have the infrastructures ready is suicide politics - the way of the Dodo.

ABS - BIOMAGNIFICATION - CANCER - CARRIER BAGS - COTTON BUDS - DDT - FISHING NETS HEAVY METALS - MARINE LITTER - MICROBEADS - MICRO PLASTICS - NYLON - OCEAN GYRES - OCEAN WASTE PACKAGING - PCBS - PET - PLASTIC - PLASTICS - POLYCARBONATE - POLYETHYLENE - POLYSTYRENE - POLYPROPYLENE POLYTHENE - POPS - PVC - SHOES - SINGLE USE - SOUP - STRAWS - WATER

This website is provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Cleaner Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company No: 4674774) 2020. Solar Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom. COFL is a company without share capital.

|